November 6, 2025

Lost Women of Science Conversations: Rosalind-The Opera

November 6, 2025

Lost Women of Science Conversations: Rosalind-The Opera

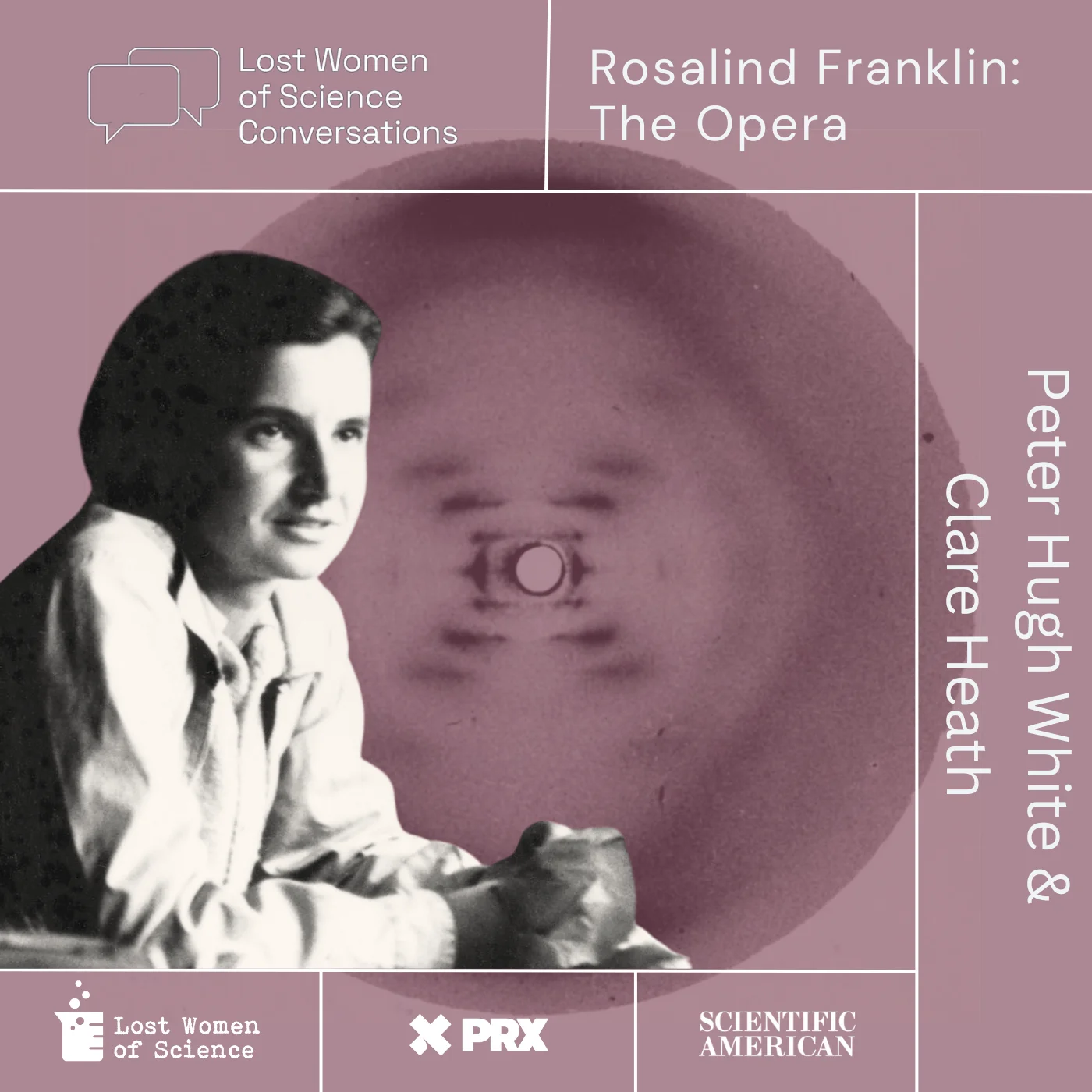

Betrayal, ambition, and the double helix: Turning Rosalind Franklin’s story and the discovery of the structure of DNA into an opera.

Episode Description

Composer Peter Hugh White and librettist Clare Heath join host Rosie Millard in front of a London audience to explore why the story of chemist and x-ray crystallographer Rosalind Franklin and the race to uncover the structure of DNA makes such a compelling subject for an opera.

We hear excerpts that capture the contrasting personalities at the centre of this scientific drama — James Watson, the brash young researcher at the University of Cambridge; Francis Crick, his more measured collaborator; and Maurice Wilkins, an anxious biophysicist uneasy about being outshone by his brilliant colleague, Franklin.

It’s a story of ambition, rivalry, and betrayal, including Franklin’s departure from King’s College London and the subsequent publication of the double helix model by Watson and Crick, which was built on insights from her work — yet without giving her due recognition.

Rosie Millard, the former arts correspondent of the BBC, is a theatre critic and arts editor. She is also chair of Firstsite art gallery in Colchester, UK and deputy chair of Opera North, a UK national opera company based in Leeds. She writes a regular substack on the arts.

Deborah Unger started her career covering technology for Business Week magazine in New York and San Francisco. She has worked for The Guardian in London and as a freelance contributor to The New York Times in Paris.

Lily Whear is a communications and strategy consultant who works with Lost Women of Science as our Director of Marketing. Lily read Chinese, History and Politics at Durham University, and is currently studying for her MBA at Quantic School of Business and Technology.

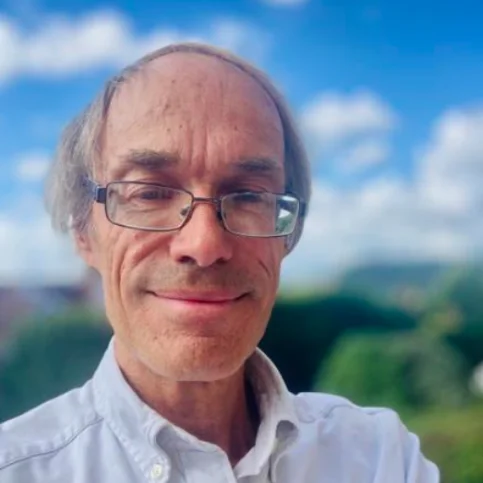

Peter Hugh White is a composer, teacher and choral scholar. He founded the Ryedale Festival in Yorkshire in 1980. His choral music has been recorded by the choirs of Christ Church and Corpus Christi College, Oxford University, among others.

Clare Heath is a retired family practice doctor who worked in London at the King’s College Health Centre looking after students and staff. She studied medical sciences at the University of Cambridge and King’s College Hospital, London. Her specialty was student health and she had special interests in medical ethics and terminal care.

Rosie Millard, the former arts correspondent of the BBC, is a theatre critic and arts editor. She is also chair of Firstsite art gallery in Colchester, UK and deputy chair of Opera North, a UK national opera company based in Leeds. She writes a regular substack on the arts.

Deborah Unger started her career covering technology for Business Week magazine in New York and San Francisco. She has worked for The Guardian in London and as a freelance contributor to The New York Times in Paris.

Lily Whear is a communications and strategy consultant who works with Lost Women of Science as our Director of Marketing. Lily read Chinese, History and Politics at Durham University, and is currently studying for her MBA at Quantic School of Business and Technology.

Peter Hugh White is a composer, teacher and choral scholar. He founded the Ryedale Festival in Yorkshire in 1980. His choral music has been recorded by the choirs of Christ Church and Corpus Christi College, Oxford University, among others.

Clare Heath is a retired family practice doctor who worked in London at the King’s College Health Centre looking after students and staff. She studied medical sciences at the University of Cambridge and King’s College Hospital, London. Her specialty was student health and she had special interests in medical ethics and terminal care.

Further Reading:

Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA, by Brenda Maddox, HarperCollins, 2002.

The Double Helix, by Dr. James Watson, Athenium Press, 1968.

My Sister Rosalind Franklin, by Jenifer Glynn, Oxford University Press, 2012.

Rosalind Franklin and DNA, by Anna Sayre, W.W. Norton, 1975.

Franklin’s Published Work, by Rosalind Franklin et al, 1949-56. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Rosalind Libretto, by Clare Heath

The cast of Rosalind as performed by the National Opera Studio in 2022.

Episode Transcript

Rosalind - The Opera transcript

Peter Hugh White: I had some doubts as to whether this story was sufficiently operatic. You know, there's no love affairs, no murders, but there's suspicion, betrayal, jeopardy, all sorts of things. The sort of core of any good opera. And the more I read about it, and the more I learned about it, the more I felt this is the perfect operatic story.

Rosie Millard: Welcome to the very first recording of Lost Women of Science in front of an audience. We are here by kind invitation of The Hearth, a London-based women's co-working and well-being space. For those of you new to Lost Women of Science, this is a podcast that tells the stories of forgotten female scientists who never got the recognition they deserved. And I'm your host, Rosie Millard.

This episode is part of the series Lost Women of Science Conversations, where we talk to writers, poets, and artists who make forgotten female scientists their subjects. And today we're going to focus on opera. The opera in question is about Rosalind Franklin and her role in the discovery of the structure of DNA.

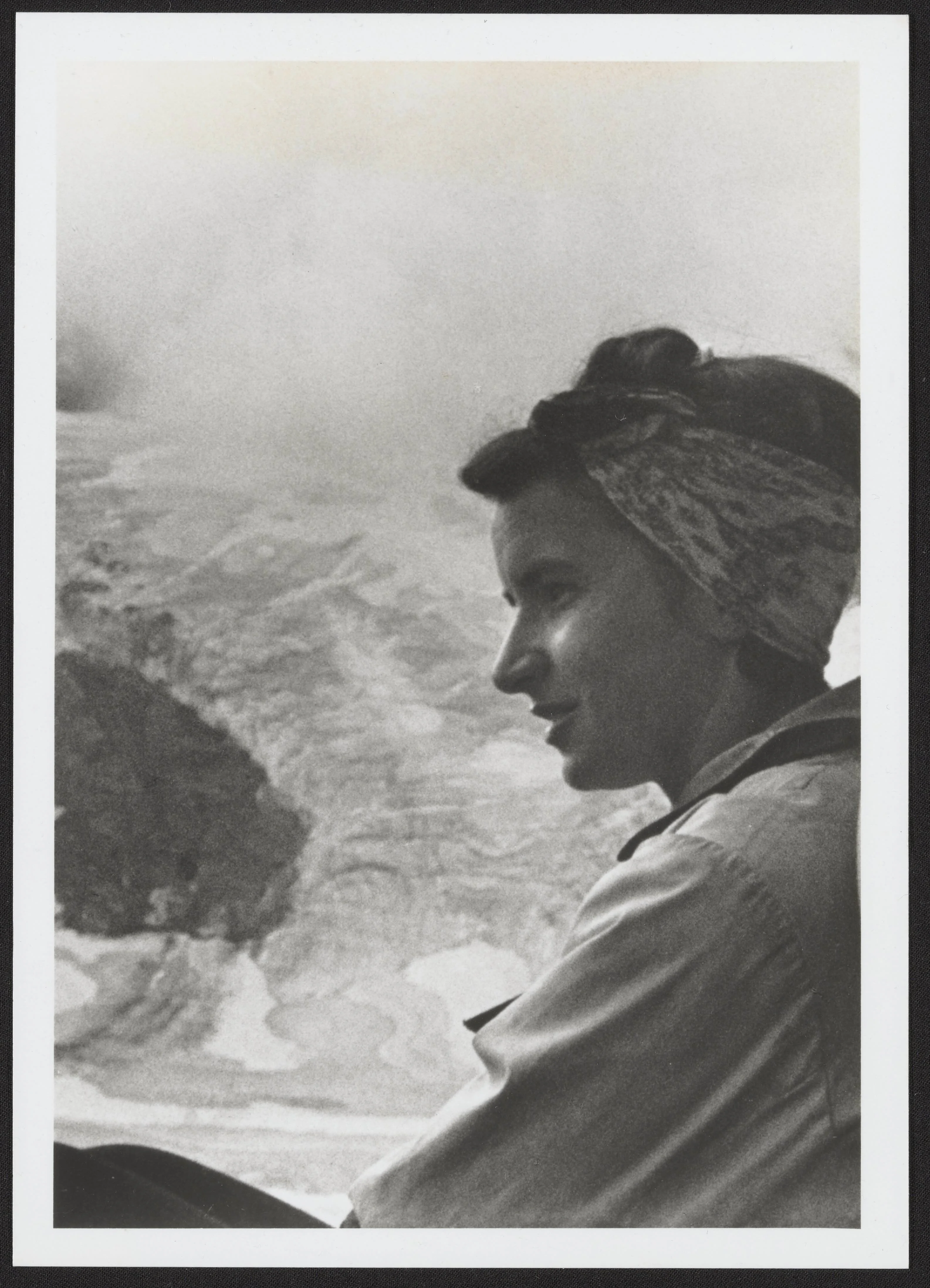

Sometimes known as the Dark Lady of DNA. It was Franklin who created the famous photograph 51 that led Francis Crick and James Watson to construct the double helix model of DNA. But for many years, her contributions went unacknowledged or were misrepresented. Although there have been biographies of Roslind Franklin since, to set the record straight, we now have an opera where music adds a very special layer to the complexity of the story.

The action takes place in the early 1950s, during Franklin's two year stint working at King's College London. This was at a time when the scientific community was in a race to uncover the structure of DNA. It's a thrilling story, and I'm delighted to welcome the composer of Rosalind, the Opera, Peter Hugh White and the Librettist Dr. Clare Heath who are going to tell us why Rosalind Franklin makes such a great subject.

Firstly, welcome Peter Hugh White. Peter is a composer and was for years Director of Music at the Royal Grammar School in Guilford. His choral music has been performed extensively in the UK and abroad, and has been recorded by the choirs of Christchurch and Trinity College Oxford. And welcome to Dr. Clare Heath. Clare is a retired GP and granddaughter of Sir Lawrence Bragg, head of the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge where Watson and Crick worked.

Clare, you've never written an libretto before. Why did you suddenly embark on this and why An opera to tell the story of Roslind?

Clare Heath: That's a very good question. I am fascinated by the story of Rosalind Franklin from an early age because of the book The Double Helix, which portrays someone who, when you go on to discover more about Rosalind Franklin, is completely unrecognizable.

Rosie Millard: Who wrote the book?

Clare Heath: James Watson. The story in Double Helix is of a difficult, trying woman. And when you read a little bit more about her and the other biographies, you realize that Rosalind Franklin was herself an extraordinary, brilliant scientist. Not in any way, uh, a downtrodden victim. She had fantastic interests in all kinds of other things. She was very capable and very clever.

Rosie Millard: But it was Watson and Crick who went on to get global fame, Nobel Prizes.

Clare Heath: Well that was because Rosalind Franklin died before the Nobel Prize was awarded. Her work was not credited to her in the Nobel speech. I think now people know that she was very involved.

Rosie Millard: So how old was she when she died?

Clare Heath: She was 37. She died of ovarian cancer.

Rosie Millard: So young. I mean, so the glories that could have come her way were denied.

Clare Heath: The day after she died was the day when she would've been announcing to an international conference, her work on the tobacco mosaic virus, which was extraordinary. And that in itself would've probably got her Nobel Prize.

Rosie Millard: So Peter, why opera? Why is opera the best vehicle for this in, in some ways. I mean,

Peter Hugh White: I think. When I go to the opera and when it's really working, it's, I call it this kind of super reality. You go through a curtain and despite the fact that it's one of the most sort of artificial art forms you can imagine.

Rosie Millard: Quite bonkers

Peter Hugh White: A bonkers art form, and yet when it works, you are transported. Absolutely. The music, if it works well, almost, it by-passes the brain. I know this brings a different dynamic. I've had some doubts after initially being so excited about the project. I had some doubts as to whether this story was sufficiently operatic. You know, there's no love affairs, no murders, but the elements. Actually for a really good operatic story, were there. There's the suspicion, betrayal, jeopardy, all sorts of things; the sort of core of any good opera. And the more I read about it and the more I learned about it, the more I felt this is the perfect operatic story.

And in some ways it's, it's such an intensely, it's almost a psychodrama. And I feel, I feel the music helps to just focus very much onto these sort of chess pieces that are moving in this story.

Rosie Millard: Alright, well let's hear some music. And in our first clip here we have Sir Lawrence Bragg, Clare's grandfather, introducing the story of the discovery of the structure of DNA.

Lawrence Bragg (sung by Gerrit Paul-Groen):

It was of course a major event, of scientific interest, yes, but also an historic contribution to human knowledge. It is a story of the researchers’ struggle of doubts and final triumph. And the poignant dilemma: would co-operation be seen as trespass? Did the idea come only to me? Or unconsciously did I learn it elsewhere? Or worse perhaps, were actions deliberate?

Rosie Millard: Peter HughWhite, that is a clip from the opera performed there by the National Opera Studio.

How did you try and, and convey the difficult, the very mathematical subject that you were embarking on? What was your approach?

Peter Hugh White: Well, I don't think I ever really thought about maths or about science so I would sort of therefore construct music that reflected those qualities. It was more really, for me, a fascinating story about a group of very disparate people. They're a splendid cast for any opera. They're so different. Watson brash, sort of firing on all cylinders, chaotic to a certain extent. And Crrick working with him at Cambridge, and then at Kings, Wilkins, much more withdrawn.

Rosie Millard: Explain who Wilkins is.

Peter Hugh White: Morris Wilkins was working on x-ray crystallography at King's and I suppose I, at the Randall Institute and where Rosalind was invited to come and join the team. And, when she came to Kings, but at the time that she was, um, sort of put in place, I think Maurice Wilkins was away and he never quite grasped what his relationship with Rosalind was going to be. Am I right, Clare?

Clare Heath: Very nearly, I would say the Randall Institute wasn't Randall Institute, then it was John Randall who was in charge at King's time. He was successful. He was a good physicist, but he somehow managed to misrepresent what Rosalind was going to do to Wilkins. And they never quite found their equilibrium, to say the very least. No.

Peter Hugh White: So you've got these very, very strong characteristics in these, in the sort of players in this, uh, opera. And so from a musical point of view, it was a gift really that as each personality developed in my mind, the music presented itself. I mean, Wilkins, the music is generally anxious, nervous. There's a, there's a deal, a, a deal of, uh, syncopation and the harmonies are rather opaque. And then if I look at Watson and when Watson and Crick are working together, I err towards the major. I don't really write major minor music, but there's a sense of it much more. flamboyant.

Rosie Millard: So it is a sort of leitmotif perhaps for each character.

Peter Hugh White: Yes. Not exactly leitmotifs, but yes, as each person sings, the music tends to reflect their character. And and I, as you've listened to the opera, I think you would be able to anticipate who was going to sing next, even if it wasn't through a leitmotif as such.

Rosie Millard: Clare, you remember your grandfather and he was obviously crucial at the whole time, the race to discover DNA. Can you explain for our listeners why DNA was so crucial? It's something we, it's a term we bandy around now, but then back in the day.

Clare Heath: Well, DNA had been discovered initially, they thought that it was a protein, uh, it was found to be, um. The stuff of genes, the stuff of heredity, um,

Rosie Millard: The backbone of life itself.

Clare Heath: Well, exactly,and no one quite understood what it was, how it could reproduce itself, how it could reproduce itself so easily and quickly. And, uh, there was a sort of gradual buildup to finding it. It was the obvious next discovery. That time in physics and microbiology, everything was suddenly becoming apparent. There was this terrific sort of new birth that discovery and DNA was the prize. This is the fifties. Rationing is still going on, and yet there's a rebirth, there's an excitement, and people were doing fantastic things,

Rosie Millard: But Rosalind is, is still working in a dismal laboratory underground. Let's hear our next clip, which is where she's going to be singing of her difficulties and the gloomy uh, surroundings in which she's forced to work.

Rosalind Franklin (sung by Alison Rose):

In this dismal room I dare to dream,

And industry masks the empty hours.

But I’m not a man, despite my work,

They cannot know or do not care

How hard it is to try and share

In their world.

Rosie Millard: Clare, you are smiling as you are listening to those words. I'm astounded that you've never written a libretto before and here you are having knocked out a, a full scale opera.

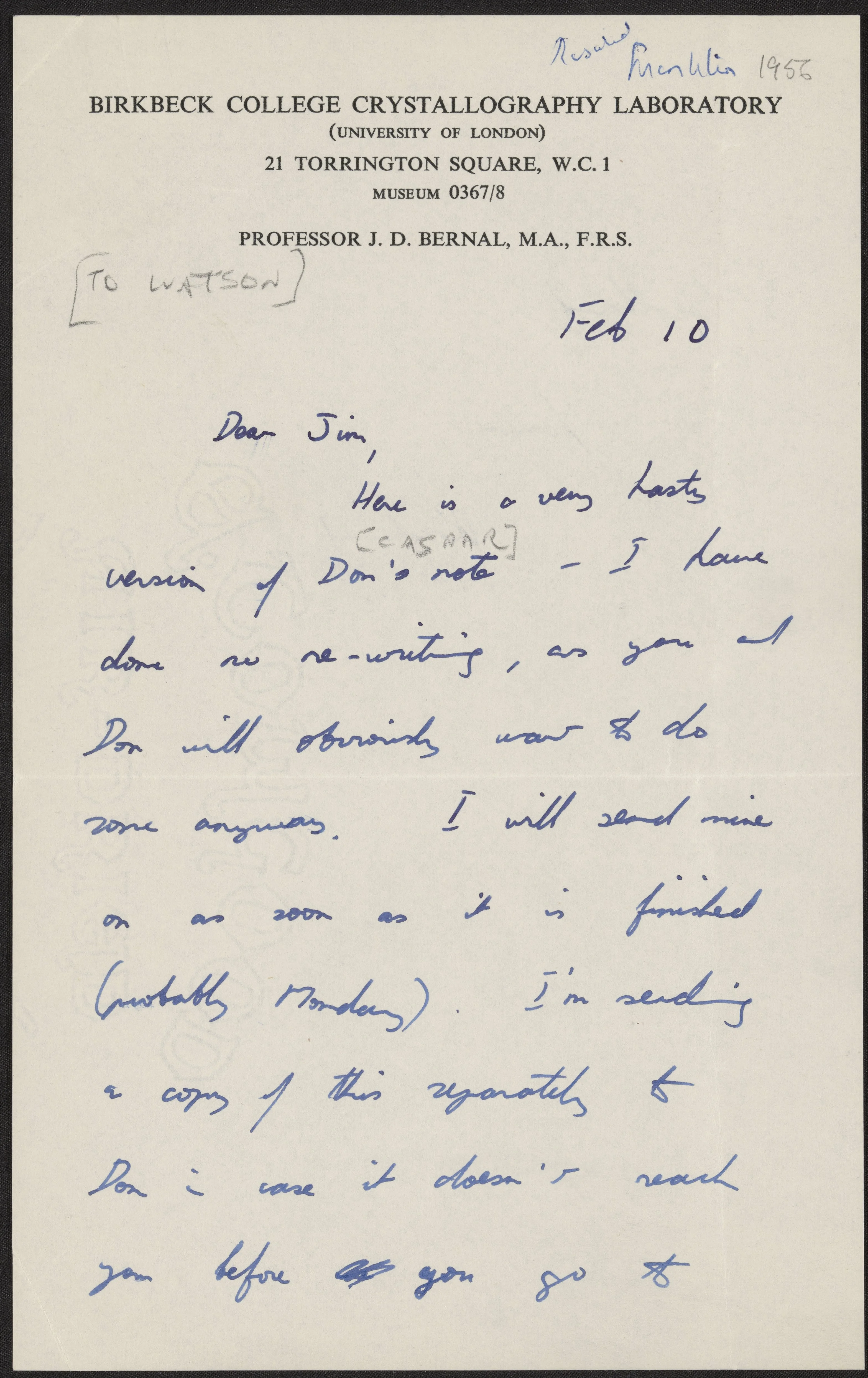

Clare Heath: There's two things there. One is that for the words I tried as often as possible to go back to actual letters, actual things almost quoting from either Rosalind or Watson or Crick. I found very helpful. Peter then battered them about to make them a little bit

Peter Hugh White. Squeeze them around a bit.

Clare Heath: To make them a bit more singable.

Rosie Millard: What I want to know though, is her story, one of sort of men ganging up against her?

Clare Heath: No. What I'm trying to tell in the story is one of a brilliant scientist who somehow got left out of the story and the men didn't gang up any more than anyone else would've done at the time. I don't think Kings at that time did have quite a few women, but in the senior common room, I didn't think women were allowed in for lunch, for instance.

Peter Hugh White: In some ways, Rosalind was the most difficult character to portray because we know that she was gregarious, fun. Outdoorsy. You know, she, she was a, a lovely person, but it's, there's no doubt that the combination of circumstances at Kings led, this led her to be, to be having a very difficult time.

Rosie Millard: Why was she known as the Dark Lady?

Clare Heath: That came from a letter that Maurice Wilkins wrote to Watson, um, describing her as ‘our dark lady,’ and I think it was just before she moved on to Birkbeck, um, because by then relationships had really broken down.

Rosie Millard: Alright, well that's a great moment to listen to our next clip, which is we'll hear Maurice Wilkins, who was Rosalind's boss and as you say, who had a difficult relationship with her singing of how hard he finds it to work with this brilliant woman.

Maurice Wilkins (sung by Aidan Smith):

Just a few steps away, but it could be a thousand miles. Her eyes transfix, but her elusive, fleeting smiles transmit no warmth. We pass, suspicious and abstracted. I had thought she would be my assistant, but no, hers is the authority, her brilliance eclipses the dull flicker of my faltering steps.

Rosie Millard: This is Lost Women of Science. Back with you shortly after this break.

Rosie Millard: Welcome back. We are here talking to Peter Hugh White, composer, and Dr. Clare Heath, librettist, of Rosalind, the Opera. Let me ask you this. There have been different depictions of Rosalind in various biographies. There was, of course, the mean-spirited version by James Watson in The Double Helix. Do either of you feel a, a kind of ethical obligation to represent Rosalind in a different way?

Clare Heath: I think that's a really good question, and I did show the original libretto to her sister. Jenifer Glynn, who lives in Cambridge; still alive, very much, quite senior now, because I was very worried I didn't want to add to the pile of insults to this already over-maligned woman scientist.

I had fewer qualms about some of the other characters. Um, but I'd hope I haven't maligned any of them too much. I wanted to present as near as I could to what actually had happened.

Peter Hugh White: We took care, didn't we, to make sure that you didn't sort of, that there were some bandwagons perhaps going around about how Rosalind was treated and, and that, and the sort of feminist drum is banged. And, and we didn't want that to happen because I think Rosalind herself, she, I think she celebrated almost when Cricket and Watson finally got it. I think we've talked about there being a race and certainly there was. Crick and Watson were damn sure they were in a race, but I don't think Rosalind was. I think she was just quietly pursuing and very carefully and diligently and with discipline.

Rosie Millard: Why did it matter that she was left out?

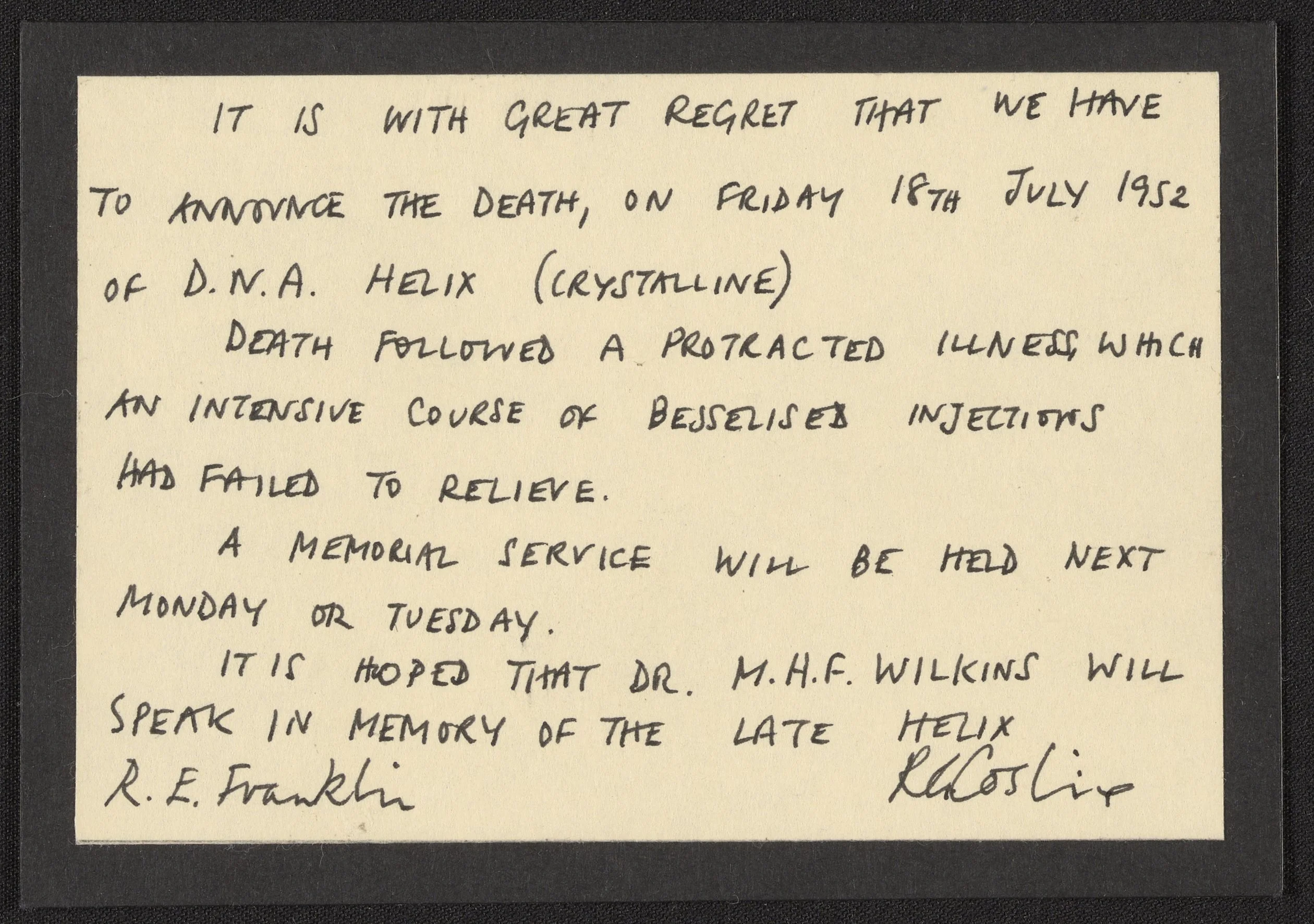

Peter Hugh White: In a sense, the moment of truth, I think is probably the reception speech for the Nobel Prize in 1963.

Clare Heath: So at the Nobel reception, it was Watson who stood up to make the acceptance speech on behalf of all three. He unfortunately failed to mention by name Rosalind Franklin. He, he made the speech on behalf of Francis Crick and of Maurice Wilkins and for himself, but he didn't say, and it is with great regret that we haven't also,

Peter Hugh White: It’s extraordinary to me also that Maurice Wilkins was there and you know that he didn't bring to the attention of, Watson and Crick that Rosalind had played such an important part.

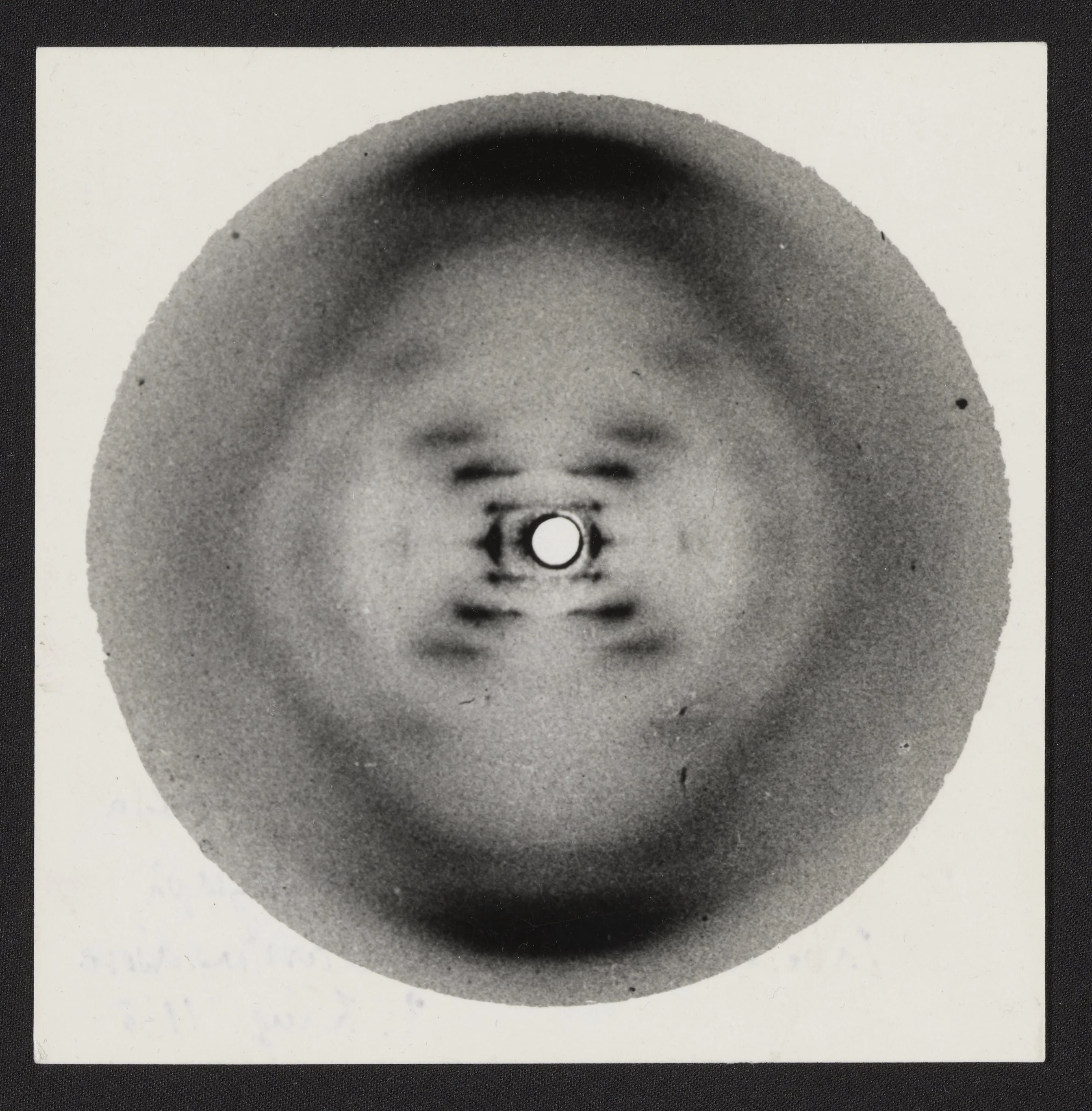

Rosie Millard: Now critically, and I think we have an image of photograph 51 here, which is the famous photograph. Can you explain this?

Clare Heath: Nervously. At the start I was imagined you were looking down, so I'm sorry you were looking down the barrel of a gun at the double helix. No. It's from the side and to an x-ray crystallographer looking at this, you can see that it is a helix, but that it's also a double helix with strands going counterbalancing to each other

Rosie Millard: To the untrained eye, and for people who are listening, it looks like an X made up by dots.

Clare Heath: This is the, the process of x-ray diffraction where you shine x-rays at a crystal, and originally Von Laue, an early 20th century scientist, noted that if you do that, they beam off in a particular way, they, they diffract and then from that, the Braggs went on to actually work out the formula for that. And using that formula, suddenly there was a whole new world of smaller things you could look at. And to x-ray crystallographers, and it's a specialist art, they can look at a picture like this and immediately say, oh, helix. But more than that, it's the fact of the pairing in it of base pairs, which everyone knew existed, but they couldn't work out how it could be.

Rosie Millard: And how long did this photograph take to make?

Peter Hugh White: I think it was about 60 hours or so. And, and indeed I think there was a power cut in the middle of this process. I can't be exactly sure how many hours he was exposed, but it was a long time.

Rosie Millard: Can you talk us through the betrayal surrounding photograph 51?

Clare Heath: Well, the photograph 51, the sort of The Double Helix story if you like, is that it was stolen from her room and shown illicitly. This isn't quite correct. Roslind was going to leave. Her work had moved on to Maurice Wilkin’s desk. It was absolutely fine for him to do what he would with it.

However, he should have said that he'd shown it and he should have acknowledged it, and he should have asked consent. That would have been fairer.

Rosie Millard: Can we say with certainty that were it not for this photograph, the true nature of DNA would not have been arrived at?

Clare Heath: It wouldn't have been arrived at by Crick and Watson, then. It would certainly have been arrived at because it was there and someone would've seen it. But this photograph helped them hugely in making their successful structure, and it was the lack of recognition that was so terribly sad.

Rosie Millard: So, this is a perfect moment to listen to Maurice Wilkins, Rosalind's boss, showing James Watson. Photograph 51

Maurice Wilkins (sung by Aidan Smith):

They were looking at this photograph, number 51. She and Gosling were working on it; I think it might be important, they were looking but not seeing. Here, this is the one.

Rosie Millard: And here's Watson's response. He's astonished at what he's looking at.

James Watson (sung by Gareth Brynor John):

My God, Wilkins, why didn’t we see it? It’s so clear, so beautiful; why did we miss it?

Oh God, it takes your breath away, so simple, so perfect; and it is a helix. Pauling thought it might be. This is a revelation.

Rosie Millard: So here we have Rosalind Franklin, PhD from Cambridge, uh, in 1945. You know, worked in Paris, as you said, worked at Kings, worked at Birkbeck. Critical work in the definition of DNA and dead at 37. It's quite a it's a story of what if, isn't it?

Peter Hugh White: Absolutely, tragic

Clare Heath: Well, I think it's what if, but she's achieved the most fantastic amount, and this is supposed to be really a celebration, not a disappointment.

Rosie Millard: There are some serious experts I know in this room, people who are very familiar with the whole story. Are there any questions you would like to ask either to Peter or Clare?

Nigel Franklin: My name's Nigel Franklin. Rosalind was my father's, the younger sister. I knew Rosalind's, uh, as a child and she died when I was seven years old. But, um, and I'd like to say thank you for doing this wonderful work. I think it's important to know that Rosalind was well-known within the science world when she was alive. And it wasn't kind of quite like, she died very soon after she stopped working on DNA and went to Birkbeck. But she left in 53 ish and she died in 58, so five years. And she was a noted authority you know. The model had been made, but she was lecturing around the world on viruses and, and indeed more than viruses. I mean, quite apart from the work DNA, which are two years of her life, which were probably the least happy time of her life and that’s the one, the time that she's most famous for.

Rosie Millard: Are there any other questions?

Julia Levy: Hello? Thank you for a really fascinating talk. Couple of questions. I'm still not clear how. You went from being a GP to writing a libretto for an opera.

Clare Heath: nor am I.

Julia Levy: Oh, wonderful. And then also how the two or you met each other?

Clare Heath:: We went on a long walk together and I said, there is this wonderful story and I think it would make a fantastic opera. And Peter being, you know, a school master and quick, said, well, I'll write it and. I am terribly lazy and busy as a GP then. And didn't. And he kept saying, well, why haven't you? I mean, where is it? Come on. And actually just before lockdown, we really got going on it. But don't you get a sort of ear thing, story that you've simply got to tell?

Rosie Millard: Just one more question.

Fabien Bryans: Thank you so much for the talk, both of you. That was really interesting. I guess like you mentioned how Rosalind Franklin lived like this really rich and interesting life. How did you decide which scenes to include in the opera so that you could tell not just a story of what happened, but also characterize these, these really interesting people in the opera?

Clare Heath:: That's a, that's an interesting question because I found it quite hard to decide, but I was telling the story of her as a brilliant scientist in this particular context. I mean, I read all around about her wonderful Alpine holidays and her friends and going off to Canada and all kinds of other areas of her life, but I couldn't fit them into four rooms in the way that this opera needs to.

Rosie Millard: Well, let's listen to the final chorus from the opera to finish the story on a musical note here. Rosalind appears as a spectre at the Nobel Prize ceremony and joins with Watson, Crick and Wilkins in celebrating their discovery. She sings: “such separate strands but intertwined. We found the key to humankind.” And then all the singers end with “And renowned be thy grave.

The Chorus and final Stanzas sung by the cast of Rosalind:

Chorus:

No exorciser harm thee!

Nor no witchcraft charm thee!

Ghost unlaid forbear thee!

Nothing ill come near thee!

Rosalind Franklin (sung by Alison Rose :

Such separate strands but intertwined,

We found the key to human kind.

Chorus:

Quiet consummation have;

And renowned be thy grave!

Rosie Millard: Wonderful. Well, the opera is going to be performed at King's College London next spring,

Peter Hugh White: Meters away from the laboratory she, she worked in, which is rather wonderful,

Rosie Millard: And possibly in Cambridge too.

Peter Hugh White: Oh, we hope very much that, uh, we and in Cambridge well, so we're really excited about the possibility of a second performance up there.

Rosie Millard: Well, I want to thank you both Peter Hugh White and Clare Heath for this wonderful conversation with us and you, the audience for your great questions. We'll all look out for the performances of Rosalind, the Opera coming up in 2026. Once again, thank you all.

This has been Lost Women of Science. I'm Rosie Millard. This episode was recorded live at the Hearth, a wellbeing and co-working space for women in London, and we thank all the wonderful people at the Hearth for making it possible. Thank you too to the National Opera Studio for permission to use its recording of Rosalind.

The episode was produced by Deborah Unger. Our thanks go to Peter Hugh White and Clare Heath for taking the time to talk with us. Mark Dezzani was our sound engineer. Lizzy Younan composes all of our music. Lily Whear designed our art [and was an associate producer for this episode]. Thanks to Jeff DelViscio at our publishing partner, Scientific American.

Thanks also to executive producers, Katie Hafner and Amy Scharf and program manager, Eowyn Burtner. Lost Women of Science is funded in part by the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the Anne Wojcicki Foundation. We are distributed by PRX. Thanks so much for listening, and do subscribe to Lost Women of Science at lost women of science.org, so you'll never miss an episode.

Listen to the Next Episode in this Series

More Episodes

Listen to the complete collection of episodes in this series.