February 5, 2026

Layers of Brilliance - Episode Two: The 'House of Magic'

February 5, 2026

Layers of Brilliance - Episode Two: The 'House of Magic'

In 1918 a young Katharine Burr Blodgett joins future Nobel Prize winner Irving Langmuir at The General Electric Company’s industrial research laboratory in Schenectady, N.Y. It’s the start of her brilliant career.

Episode Description

Katharine Burr Blodgett arrives at The General Electric Company’s legendary research laboratory in Schenectady, New York, known as the “House of Magic.” She was just 20 years old when she entered a world built almost entirely for men. She joins as assistant to the brilliant and eccentric Irving Langmuir, a star chemist whose fundamental work in materials science and light bulbs would bring fame to him, and fortune to GE.

The General Electric Company was an obvious choice for a brilliant young scientist. But was it the promise of scientific discoveries that drew Katharine to Schenectady or the need to confront the personal tragedy that marked the place where her own story began? Perhaps it was both.

Katie is co-founder and co-executive producer of The Lost Women of Science Initiative. She is the author of six nonfiction books and one novel, and was a longtime reporter for The New York Times. She is at work on her second novel.

Natalia is a Peruvian journalist, editor, and writer based in Philadelphia. Her work focuses on gender inequality, labor issues, and reproductive rights. Natalia has worked as an editor for Radio Ambulante at NPR and in 2021, she won the Aura Estrada International Literary Award. She is currently working on her first book.

Sophia Levin is a journalist and teacher based in Washington, D.C. and Pittsburgh, PA. She has written about unions, infrastructure, and reproductive healthcare for The Tartan and PublicSource. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Creative Writing and History from Carnegie Mellon University.

Hannah is a Boston-based journalist with a background in storytelling, production, and strategic communication. She has reported on a variety of topics, including arts, culture, finance, and relationships between municipal agencies and communities. She studied journalism and art history at Northeastern University.

Katie is co-founder and co-executive producer of The Lost Women of Science Initiative. She is the author of six nonfiction books and one novel, and was a longtime reporter for The New York Times. She is at work on her second novel.

Natalia is a Peruvian journalist, editor, and writer based in Philadelphia. Her work focuses on gender inequality, labor issues, and reproductive rights. Natalia has worked as an editor for Radio Ambulante at NPR and in 2021, she won the Aura Estrada International Literary Award. She is currently working on her first book.

Sophia Levin is a journalist and teacher based in Washington, D.C. and Pittsburgh, PA. She has written about unions, infrastructure, and reproductive healthcare for The Tartan and PublicSource. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Creative Writing and History from Carnegie Mellon University.

Hannah is a Boston-based journalist with a background in storytelling, production, and strategic communication. She has reported on a variety of topics, including arts, culture, finance, and relationships between municipal agencies and communities. She studied journalism and art history at Northeastern University.

Peggy Schott is a retired chemist from Northwestern University and has written about Katharine Burr Blodgett and her achievements.

Ginger Strand is an American author of nonfiction and fiction. She is the author of the 2015 nonfiction book, The Brothers Vonnegut: Science and Fiction in the House of Magic.

Bill Buell is the official county historian of Schenectady County, as well as a long-time reporter for the Daily Gazette.

David Kaiser is a professor of physics and the history of science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

George Wise is a former communications specialist at the GE Research and Development Center in Schenectady. He is also a historian of science and technology, and the author of The Old GE (2024).

Cyrus Mody is a historian of recent science and technology and is a professor of the History of Science, Technology, and Innovation at Maastricht University in the Netherlands.

Chris Hunter is the curator and president of the Museum of Innovation and Science in Schenectady, New York. He is a leading authority on the history of electrical and electronic technologies and has curated numerous exhibitions at the Museum.

Maryanne Malecki is a career educator in history and language arts, and offers “ghost tours” of Schenectady through the Schenectady Historical Society during the month of October.

Further Reading:

The Brothers Vonnegut: Science and Fiction in the House of Magic, by Ginger Strand, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2015.

The Remarkable Life and Work of Katharine Burr Blodgett (1898–1979), by Margaret E. Schott, E. Thomas Strom, and Vera V. Mainz from In The Posthumous Nobel Prize in Chemistry Volume 2, Ladies in Waiting for the Nobel Prize 1311, 1311:151–82. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society, 2018.

American Women of Science, by Edna Yost, Frederick A. Stokes Co, 1943.

The Old GE 1886-1986, by George Wise, Schenectady Historical Society, 2024.

Electric City: General Electric in Schenectady, by Julia Kirk Blackwelder, Texas A&M University Press, 2014.

Episode Transcript

Layers of Brilliance - Episode Two: The House of Magic

Maryanne Malecki: That particular house on Front Street, there was something about it that people didn't want anybody to know the story. So I, of course, looked it up.

Ginger Strand: Schenectady must have been so fraught in a way for her.

Bill Buell: It's strange that Katharine came back. I mean, she had no memory of her father. She must have felt a connection, 'cause she came back to work for GE.

Maryanne Malecki: You know, when you lose someone. You try to look for as many connections as you possibly can.

Katie Hafner: I’m Katie Hafner, and this is the Lost Women of Science. Today on Layers of Brilliance, a young Katharine Blodgett is determined to work at the General Electric Company in what's basically a scientist's dream: a research lab where pure science is king. And there's an extraordinary man there: the chemist, Irving Langmuir, who will support and mentor her. But in many ways, Schenectady, New York is the last place you'd think Katharine would go if you knew what had happened to the Blodgetts in that city two decades earlier.

Last summer, producer Sophia Levin and I visited Schenectady, where Katharine Blodgett lived for more than 60 years. Our first stop, an easy walk from our Airbnb, was the neighborhood where her boss, Irving Langmuir, lived on a quiet tree-lined street in what's called the GE Realty Plot––75 acres that the General Electric Company bought many moons ago from adjacent Union College in order to build houses for its high-level executives.

This is the house. Isn’t it lovely? Ah, let’s see…

1176 Stratford Road, where Mr. and Mrs. Irving Langmuir are said to have entertained the likes of Niels Bohr, Ernest Rutherford, and Charles Lindbergh, is a classic 20th-century style, known as Colonial Revival, with columned front porch––symmetrical and stately. A little formal maybe, but warm at its core. A magnificent Japanese maple dominates one side of the front yard. You can imagine walking into a house like this and feeling as if you've really made it.

And because the 1920s belonged to an era that was sprinting into the future, and the Langmuirs lived in the backyard of the very company that was inventing the tools for that sprint, well, you can imagine the thrill there must have been at the prospect of domestic upgrades—not just at 1176 Stratford Road, Schenectady, New York, but everywhere in America.

A GE-made electric refrigerator replacing the icebox, telephone mounted proudly in the hallway, eventually a state-of-the-art GE television set and washing machine.

Sophia and I were lingering outside that house early in the morning, allowing ourselves to daydream about what it might be like to live in a home like that, when we spotted a woman leaving her house across the street to walk her dog.

Katie Hafner: Excuse me. Hi. Do you know much about this house?

Maryanne Malecki: What did you wanna know? It was Irving Langmuir’s house.

Katie Hafner: Right. And do you know much about him?

Maryanne Malecki: Well, he was a physicist.

Katie Hafner: Right.

Maryanne Malecki: He won the Nobel Prize—

Katie Hafner: Yes. Yeah. And do you know, did you know anything about his colleague, Katharine Burr Blodgett?

Maryanne Malecki: No. No.

Katie Hafner: Yeah, she was maybe even smarter.

Maryanne Malecki: Always, women are smarter.

Katie Hafner: Ooh, I wanna hang out with her.

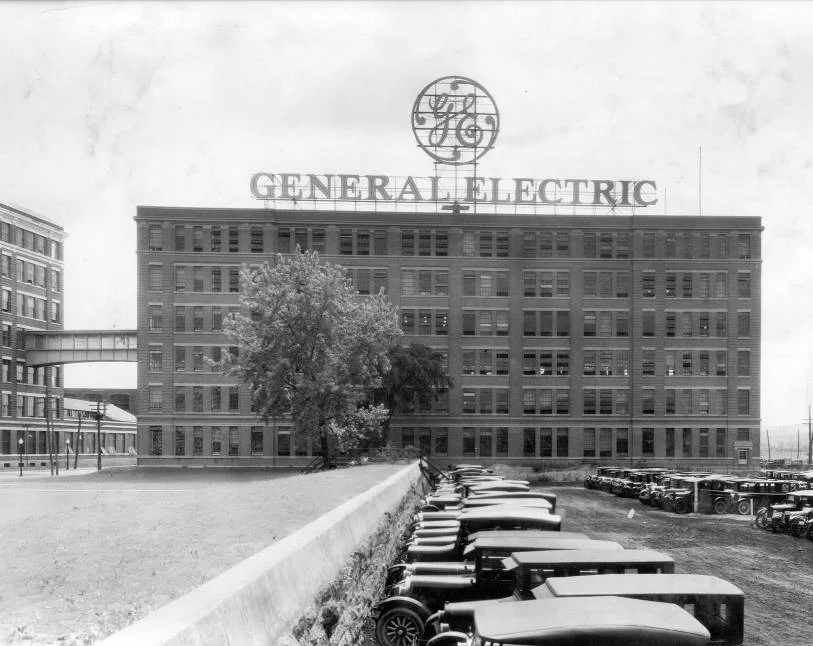

Our new friend's name is Maryanne Malecki, a native Schenectadian who knows a lot about Schenectady’s past and present. She leads us on a tour of the neighborhood, giving us a running account of the city's ups and downs through the years. Back in the early 20th century, the General Electric Company wasn’t just in Schenectady; it was Schenectady. The city even earned the nickname “Electric City.” Tens of thousands of workers clocked in at massive factory complexes. The company built neighborhoods for its employees. Your father worked at GE, and you probably expected you’d work there too. And during World War II, a sizable fraction of Schenectady’s residents worked at GE. Maryanne is telling us all of this as we walk down the street lined with red and white oak trees, hemlocks, and maples.

Maryanne Malecki: There were three department stores, plus specialty stores, plus, I don't know how many, half a dozen jewelry stores. And this goes into, well, probably into the sixties, late sixties, early seventies. When the company pulled out, Schenectady’s fortunes were left, you know, demolished.

Katie Hafner: Today, the number of GE employees in Schenectady has shrunk dramatically. Some neighborhoods still haven't recovered from the decades of decline. The city is still trying to figure out what comes next when your entire identity was built around one massive employer that's mostly gone. But you can still see the old Schenectady in the city's bones.

When Katharine arrived in the fall of 1918, she chose to live across town from the GE Realty Plot in the historic Stockade District, which still has many of the architectural gems from the early 1900s that tell you this place once had serious money flowing through it. Schenectady, New York was exactly where Katharine Blodgett wanted to be. But why? Why, when it came time to look for a job in her senior year of college, did she entertain the General Electric Company and only the General Electric Company?

Women didn't have it easy to be sure, but Katharine was a star, and she could have joined the faculty at a college somewhere. And if it was a corporate research job she was looking for, why didn't she even want to explore Westinghouse in Pittsburgh? Or Bell Labs, which would've put her in New York City, where she'd grown up.

Katie Hafner: In fact, once we learned more about Katharine's story, we expected that Schenectady, New York, would be the very last place she'd want to go.

Maryanne might not have recognized Katharine's name, but like a lot of Schenectadians, she knows all about one of the city's most enduringly gruesome tales. She just hadn't made the connection between the Katharine Blodgett we just asked her about, and that story.

Maryanne Malecki: The reason I know this story is because last year I did the walking tours, we call them the “ghost tours” in the Stockade. But that particular house on Front Street, there was something about it that the people didn't want anybody to know the story. So I, of course, looked it up.

Katie Hafner: To understand the pull Schenectady had on Katharine, we need to return to December 1897, just a month before Katharine was born. Her parents had moved to Schenectady three years earlier, shortly after their marriage.

Imagine you are Katharine's mother, Katharine Burr. You are pretty proud of yourself for having landed the handsome George Redington Blodgett: a Yale graduate from a fine New England family. He's a patent lawyer, already a star at the General Electric Company. Yours is a true romance. It seems like just last week that you were receiving the warmest of wishes from all quarters for your engagement, and it seems just yesterday that you and your husband were settling into your grand new house in Schenectady’s lovely, leafy Stockade District. One night in December of 1897, you go to bed, happy, fulfilled, in love, expectant.

You are 27, your husband is 35. Although your first child didn't survive past his infancy, your second boy is now a toddler, and you're pregnant again, due very soon.

Imagine then, that a crime happens late that same night in your haven of a home, a crime so unspeakably heinous that to this day, Schenectadians recount it as if it is still fresh, as if the tragedy befell not just one household, but all of Schenectady.

Bill Buell: I know it was 1897, but still, you could get a sense, an eerie sense of something bad happening there. Even if it was 127 years ago.

Maryanne Malecki: It was at night. Mr. and Mrs. Blodgett were already in bed. Mrs. Blodgett heard a noise, so she told her husband to get up.

Chris Hunter: George Blodgett confronts the burglar, gets shot, but doesn't quite realize it right away.

Maryanne Malecki: He stumbled through the doorway––

Chris Hunter: And then actually goes downstairs to chase him.

Bill Buell: And then he realizes he is badly hurt. And at that point, he collapses, so the guy escapes out of the house.

Maryanne Malecki: Mrs. Blodgett, she's got a young child sleeping in the next room, was very close to giving birth to their second child.

Julia Kirk Blackwelder: She was panicking.

Chris Hunter: She apparently had a gun,

Maryanne Malecki: Opened the window,

Bill Buell: And shoots a gun four or five times just to alert the neighbors.

Chris Hunter: Her plea for help. The police bring a surgeon in.

Maryanne Malecki: From Albany within 55 minutes.

Peggy Schott: He survived for a short time, but uh, the medical care wasn't sufficient, and he did pass away.

Maryanne Malecki: They never found the person who did it.

Julia Kirk Blackwelder: What I think of is the terror and horror that the wife experienced. It's a wonder she didn't lose the child.

Peggy Schott: Mrs. Blodgett wore black for the rest of her life.

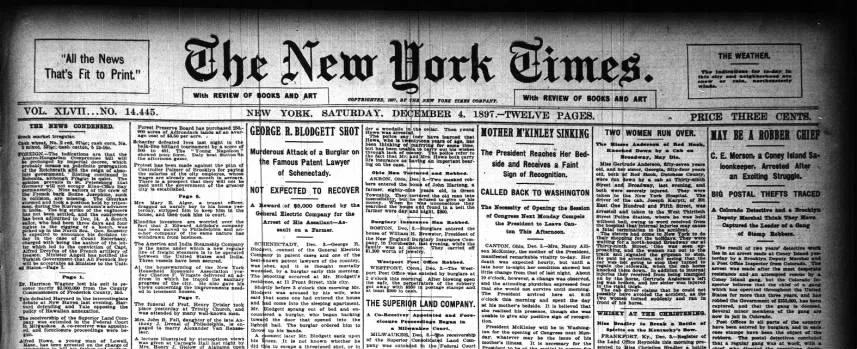

Katie Hafner: News of the murder spread quickly. Within hours, the story was on the front page of the New York Times, the headline, “Murderous Attack on the Famous Patent Lawyer of Schenectady.” Another newspaper carried a detailed artist's rendering of the murder scene. GE offered a $5,000 reward for the apprehension of the killer, and the company's head lawyer called the loss of George Blodgett, who had no equal in electrical patent law, “Absolutely irreparable.” Someone was arrested but he died in jail before charges could be brought. The murder remained unsolved.

Katharine Burr, by the way, lived to the age of 95.

We haven't been able to confirm that she wore black for the rest of her life, but we do know that she never remarried. And we know that she was very, very close to her daughter Katharine. They were in constant touch. They were mutually protective of each other. Because when something like that happens, you close ranks, you gather around you what's most precious, and you do that for the rest of your living days.

A month after the murder, Katharine Burr gave birth to Katharine, and five weeks after that, she moved with the two children to New York City, where she had family. And you might think that this is the last that she or her children would want to see of Schenectady, New York. But, two decades later her daughter, Katharine Burr Blodgett, moved back. We could find only one––decidedly cryptic––reference to Katharine's reason for returning to Schenectady. Late in her life, she sat for a brief oral history for GE and she said, only this, “When I graduated from college, I needed a job, and my father had been in the General Electric company, and I looked in that direction.”

Ginger Strand: The place must have been so fraught, in a way, for her, although she didn't have memories of her father.

Katie Hafner: That's Ginger Strand, an author who's written extensively on Schenectady and the GE Research Lab.

Ginger Strand: You know, she strikes me as a very pragmatic person, right? But then again, perhaps she was looking to reclaim some of her past, some of her history, and turn it into something more positive.

And here’s Bill Buell, historian for Schenectady County.

Bill Buell: It's strange that Katharine came back, I mean, she had no memory of her father. She must have felt a connection.

Katie Hafner: Connection was what she could well have been seeking because not only did Katharine move back to Schenectady, but she moved quite literally around the corner from where her father was killed, and eventually she bought a house that was essentially across the street, where she lived until shortly before her death in 1979.

In 1972, 7 years before she died, Katharine was interviewed by Larry Hart, a local historian.

Larry Hart: Well, Dr. Blodgett, I'll just pull this chair up here. And we're at your, your home at, uh, uh, 18 North Church, Downtown Stockade area.

Katie Hafner: Then he cut straight to the chase.

Larry Hart: Now, um, I might as well get this over with, I wanted to talk to you a little bit more about your father…

Katie Hafner: And he might've been a little nervous about it because listen to this gaff.

Larry Hart: Now, of course, uh, you died––

Katie Hafner: Oops!

Larry Hart: Or, I mean, your, your father died before you were born.

Katie Hafner: We're hearing this on an audio cassette, so we can't see the expression on her face, but she seems to just be going along with it.

Larry Hart: Do you any, um, memories, um, however unpleasant they may be, that your mother had of this incident? Did she ever say much to you about it?

Katharine Burr Blodgett: No, she didn't talk to me about it, but I didn't ask her questions.

Katie Hafner: She didn't ask about it, and her mother didn't talk about it, at least not directly because then Katharine says this.

Katharine Burr Blodgett: I overheard when she was talking to other people.

Katie Hafner: Maybe, just maybe, Schenectady, New York and General Electric were Katharine's destiny. Maybe her brief life to date had been building to that moment when she would walk through the door of building five at the huge GE complex and pick up, in a sense, where her father had left off. And maybe part of that call of fate was to work for the brilliant, but odd, and never boring Irving Langmuir.

More after the break.

Katie Hafner: In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a new kind of space began taking shape inside America's biggest companies. The Industrial Research Lab. By the early 1900s, firms like General Electric, Westinghouse, AT&T and DuPont had begun formalizing laboratory work, turning research into an institutional priority.

The idea was that the companies would set up these research labs, attract highly talented scientists, and give some of them broad autonomy. They had the best of both worlds. While there was still some pressure to commercialize their findings, scientists like Irving Langmuir could steer their research toward topics that interested them as well as patent their work––a clear gain for the company they worked for––and get recognition within the scientific community, making this opportunity a tough one to pass up.

David Kaiser: You have many accounts of really leading researchers when they show up at places like GE Labs or Bell Labs or Westinghouse. Saying, my goodness, this is like an oasis.

Katie Hafner: That's David Kaiser, the science historian you heard in episode one.

David Kaiser: There's remarkably talented people. There's seemingly, you know, remarkably generous funding and resources and instrumentation. And sometimes the universities couldn't even compete. And that went on for a long, long time.

Katie Hafner: In her book,“The Brother's Vonnegut: Science and Fiction in The House of Magic,” Ginger Strand describes the history of the research lab at the General Electric Company, where both the writer Kurt Vonnegut and his brother Bernard worked. House of Magic, by the way, was the longtime nickname for the GE Lab.

Ginger points out that not all corporate labs let their scientists play the way GE did, and focused more on inventions they could commercialize AT&T’s Bell Laboratories for one.

Ginger Strand: If you went to Bell Labs, you were, you know, pushing forward communications so that you could invent new products for Bell Labs to sell.

Katie Hafner: But GE took a different approach. Or at least, that's what the company told its new recruits,

Ginger Strand: They said, you know what? We'll just let you do whatever you wanna do.

You can write papers and deliver them at conferences. You can just be a scientist and we're gonna trust that inventions will come out of that naturally. And they did. They really did. It was a great place to work because you didn't have pesky undergraduates hanging around, you didn't have to give lectures and serve on committees the way academic scientists did.

Katie Hafner: Pure Science was what Irving Langmuir, not yet 30 years old, was after when he started working at GE's Research Lab in 1909.

No sooner did Irving Langmuir arrive at GE than he went straight to work on one of the most intractable problems of the early 20th century, improving the performance of light bulbs––or lamps, as they were called.

Before Irving Langmuir came along, incandescent bulbs contained a vacuum. That is, all the air was removed from the bulb. This vacuum was meant to prevent the tungsten filament––that’s the little wire inside the bulb, the thing that glows––from burning up and disintegrating immediately, which is what a very hot piece of metal would do in the presence of oxygen.

But in a vacuum, the filament had another problem. Its atoms, tungsten atoms, would just evaporate when they got hot. These tungsten atoms would then condense on the slightly cooler inside of the glass bulb, blackening it and dimming the light over time. It also limited how hot and thus, how bright and efficient the filament could get. Plus, these bulbs were costly to make. So it was an economic trade-off that both businesses and customers had to calculate when it came to lighting. After three years of working on the problem, Irving had a breakthrough.

He did something ingenious. He flooded the bulb with nitrogen and argon, those are inert gases, and their presence significantly reduced the vaporization of the filament. Then he coiled the previously straight tungsten filament into a helix, which trapped the heat emitted from the filament kind of like a scarf. Slowing down the rate at which heat left the bulb prevented the filament from burning out as quickly.

Langmuir's incredible innovation took bulbs that typically lasted only a few hundred hours and pushed them into the thousand-plus-hour range, all while making them shine brighter and last much longer.

The gas-filled, coiled filament design marked the true beginning of the modern incandescent bulb. It was so successful that it became the global standard almost overnight, and helped solidify GE's dominance in lighting.

Of course, we’re moving into the LED era, but Langmuir’s design reigned for more than a century.

GE ad: There is scarcely a person living today who is not benefited by Langmuir's gas-filled incandescent lamp, which turns night into day, estimated to save the American people a million dollars a night.

Katie Hafner: And over the course of one of those million-dollar nights, Irving Langmuir had become GE's golden boy.

Over the years, he would come up with some pretty cockamamie science, but then land on something brilliant. And in the dubious distinction category, Kurt Vonnegut, who worked in GE's News Bureau for about four years, even modeled the main character in his novel “Cat's Cradle” after Langmuir.

The fictional Felix Hoenikker is the father of the atomic bomb, which by the way, Irving Langmuir was not. The Langmuir-slash-Hoenikker character is exceedingly absent-minded, which by the way, Irving Langmuir was, or maybe he was just hyper-focused.

The Hoenikker character, who abandons his car in a traffic jam one day and walks the rest of the way to work, and well, here's a snippet from the audio version of Cat's Cradle, told from the point of view of one of Hoenikker’s/Langmuir’s children.

Audiobook clip: Did you ever hear the famous story about breakfast on the day mother and father were leaving for Sweden to accept the Nobel Prize? Mother cooked a big breakfast, and then when she cleared off the table, she found a quarter, a dime, and three pennies by father's coffee cup. He'd tipped her.

Katie Hafner: Which takes us back to last summer and our amble through Irving's old neighborhood.

We've just spent a good hour with Maryanne and her dog, Caleb, and I've bent Maryanne's ear about Katharine, some of the treasures we've found, pointing to her love of experimentation, with everything in her life.

Katharine was an intrepid baker of popovers, And for years she tinkered with the recipe's variables.

She was constantly measuring the pH level of the soil in her garden. In her personal diary, she recorded the high and low temperature and humidity every single day of the year, and, I tell Maryanne, she had no qualms about turning to experts for advice.

Katie Hafner: She was a big gardener. And she wrote a couple of letters, one to the New York State agricultural, whoever, and it just says, “Dear Sir,...”

I mean, this is this brilliant physicist, right?

“My lettuce is wilting, I've noticed, but if I mix this amount of water plus manure...”

I mean, she's basically talking about fertilizing.

Maryanne Malecki: Right, right…

Katie Hafner: And I just love that. I love that her—

Maryanne Malecki: It's the humanity.

Katie Hafner: The humanity and the curiosity.

Maryanne Malecki: Yes. Hey, we all have to clean the cat litter, you know? Yeah. No matter how brilliant we are, we have to clean the cat litter.

Katie Hafner: Actually, Katharine didn't have a cat or any pets as far as we know, but I get what Maryanne's saying.

Maryanne Malecki: Alright, nice to meet you. Bye. You so much. Bye-bye.

Katie Hafner: After we drop Maryanne and Caleb back at their house we find ourselves standing across from the grand Langmuir domicile where that mythical tip was left. And I'm put in mind of something Ginger Strand said the first time we spoke with her.

Ginger Strand: I see Irving Langmuir as almost a tragic character. He was such a brilliant scientist, did such powerful work in his early years. Even critiqued other scientists for their, what he called pathological science, their willingness to follow their desires instead of the science into rabbit holes of untruth. And he himself ended up going down a similar rabbit hole.

Katie Hafner: Which makes me think of Katharine and her rigorous, systematic approach to her science, making them quite an unlikely duo.

You're going to hear more about two of Langmuir's pretty embarrassing rabbit holes. And Katharine's studious avoidance of one in particular. So who was this guy, Irving Langmuir? And what's his story?

Irving Langmuir was born in Brooklyn, New York, on January 31st, 1881, making him almost exactly 17 years older than Katharine Blodgett.

Irving was the third of four brothers, and the Langmuir boys were tight. They skied together, hiked, and climbed mountains together. Irving, in particular, wasn't merely an outdoorsy type, he was the type who went snow camping and loved it.

Their father, Charles, had high expectations of his sons, especially Irving. Charles Langmuir was no fan of his son's weakness in grammar and spelling.

Our favorite piece of evidence, which we found among Irving's papers during our visit to the Library of Congress, was a withering letter Charles Langmuir wrote in 1896 when Irving was 15. Irving had spelled the word Bible B-I-B-A-L.

BEE-Ball

And his father pounced: “You had better learn how to spell that word he wrote and not make that mistake again.” It appears that Irving’s struggles with the basics of English grammar and spelling trailed after him well into adulthood. Irving's father died in 1898, 2 years after the scathing “Bibal” letter, but already when he was a young boy, little Irving Langmuir, bad grammarian and egregious speller, had a gift. And that gift was for science, especially chemistry.

By the time he was 12, he was spewing chemistry ideas to just about anyone, interested or not. And once he was acknowledged as the scientific genius of the Langmuir family, there was no question how the rest of his life would unfold. He attended The School of Mines at Columbia University, where he graduated with a degree in metallurgical engineering in 1903. From there, he headed to Germany and the pinnacle of scientific study, the University of Göttingen.

Here's Cyrus Mody, the historian we heard from episode one.

Cyrus Mody: American science at this point was really seen as pretty immature. You know, if you wanted a PhD, really you had to go to Europe.

Katie Hafner: David Kaiser agrees.

David Kaiser: Not only Germany, but certainly to the continent, either to Britain, but especially to the continents, not to stay in the United States, that's for sure.

Katie Hafner: As he neared the end of his studies, Irving faced a decision: should he become a commercial chemist like his eldest brother Arthur, and rake in money, or should he commit to pure research?

That's when his older brother Herbert stepped in, with a lengthy letter he wrote in 1904 while Irving was still in Germany. That letter may well have changed his little brother's life, and the course of scientific advancement in the United States.

Sure, Herbert wrote to Irving, go into business, make a lot of money. If that is, you're a run-of-the-mill chemist, like your brother Arthur.

Here’s Benjy, our resident dramatist who’s doing voiceovers for us this season in the role of Herbert Langmuir: the wise older brother.

Benjy Wachter as Herbert Langmuir: And yet, you know, and I know that money is not the great source of happiness if you are the exceptional man. It is, in my opinion, your duty to be one of the pioneer scholars in America.

Katie Hafner: Then Herbert really got into it, growing downright impassioned.

Benjy Wachter as Herbert Langmuir: And the minute you allow yourself to deviate from the path of pure science, you'll lose something in character and more still, in the power to aspire and the possibility to be truly happy.

Katie Hafner: So Irving chose academia, which, in the most convoluted of ironies, turned out to be the worst decision he could possibly make. He finished up his PhD in Germany.

George Wise: And he came back and he got a job at Stevens Tech.

Katie Hafner: That's George Wise, a retired GE technical writer and unofficial GE historian. The Stevens Tech George is referring to is Stevens Institute of Technology in Hoboken, New Jersey, where Irving was hired as an instructor in the chemistry department.

George Wise: And he was very much overworked as a teacher. He got no assistance. He hardly published anything.

Katie Hafner: In other words, the advice so ardently given by Herbert, and so gratefully taken by Irving, to reject business in favor of a university position so that he could do science to his heart's content, turned out to be dead wrong.

For the entire three years he was there, Irving was miserable. He hated everything about the job: his workload, his students, his pay. He wrote lengthy letters of complaint to his mother. Then, says Ginger Strand, he discovered the plum that was GE's research lab.

Ginger Strand: He took it on as a summer job while he was still at Stevens, and then he., he quickly realized, oh, this is a pretty good deal.

Katie Hafner: Then he jumped, straight off the teaching treadmill and into the arms of GE, the embodiment of capitalism, American style, and in 1909, at GE and beyond, that meant, well, a masculine place, for men. And a particular mold of men at that. Here's science historian Cyrus Mody.

Cyrus Mody: Some of these laboratories had proudly discriminatory, uh, hiring practices. Bell Laboratories, for instance, really preferred to hire men from the Midwest, and, um, really preferred not to hire Jews. So I would guess that there was a similar steep hill in terms of hiring women.

Katie Hafner: Women, if they worked at the lab at all, were typists or computers, i.e., human calculators or secretaries. And then into that den of exclusion, waltzes 20-year-old Katharine Blodgett, hired as a full-fledged scientist, excited to start working for Irving Langmuir.

Just two years earlier, he'd come up with something even more groundbreaking than his light bulb work. It was what he would win the Nobel Prize for, and for Katharine, it was the very thing that would lead to her most important discovery. It was something called self-assembled monolayers. In the 1910s, Langmuir had grown fascinated with how certain substances behaved at the interface between air and water, working with oils, fatty acids, and soaps spread in exceedingly thin films on water, he discovered something radical. When these molecules were spread across a clean water surface, they naturally organized themselves into monolayers. Those are single-molecule-thick sheets, and there was more. Langmuir showed that the molecules oriented themselves in a consistent way, looking like little tadpoles with the hydrophilic head, the end that likes water, toward the water, and the hydrophobic tail, the end that dislikes water, sticking up into the air. He found that these monolayers had measurable physical properties, including surface pressure, and that their behavior could be systematically controlled by compressing the film with a movable barrier. This gave physical chemistry its first truly quantitative way of studying surfaces.

All of this, he laid out in a landmark paper in 1916, which is often cited as the foundational document of surface chemistry. He had demonstrated the existence of monolayers unequivocally with precise measurements, transforming these thin films from a curious laboratory trick into a disciplined scientific measurement technique. From there, scientists could better understand the structure of molecules and how they arrange themselves on liquid surfaces, which can lead to the creation of new materials. Katharine arrived just after Labor Day in 1918 for her first day of work at GE’s mammoth, sprawling complex.

Ginger Strand: GE would still have been growing when Katharine Blodgett arrived, and Schenectady as well.

Katie Hafner: That's Ginger Strand again.

Ginger Strand: She would've arrived to a fully formed company town life that included work and off-hours: work and play. It was the American dream, really.

Katie Hafner: Coincidentally, GE’s campus was almost exactly the size of Bryn Mawr's, but that's where the resemblance ended. The soaring gray stone buildings and grassy lawns of Bryn Mawr were replaced with GE’s closely packed machine and blacksmith shops, buildings for making enamel and porcelain products, gas and oil houses. U.S. manufacturing at its finest in the early 20th century.

Katharine's first professional home was the third floor of Building 5, a seven-story brick edifice lined with wide windows smack-dab in the middle of the GE factory. Lest you should picture young Ms. Blodgett in an office in the traditional sense, think desk, desk lamp, chair, credenza.

Here's what her workspace probably looked like: a sturdy workbench designed for holding equipment, chemicals, and ongoing experiments. Cabinets for storage of glassware, and a general clutter of beakers, wiring, and machinery. The focus was on function. The lab designed for action, and the environment was noisy, with motors operating nearby to power machinery and oh, no chair. Or if there was a chair, it would be an armless lab stool, something that can be easily moved or tucked away. The work demanded mobility and vigilance. Chairs were for other people. The lab employed 275 people at all levels of pay, education, and responsibility. Young boys cleaned test tubes, brawny machinists built gauges and mills, and scales delicate enough to weigh an inch of a spider's web. And then of course there were the scientists, Irving Langmuir at the top of the heap.

Add to that Katharine Burr Blodgett, four months shy of her 21st birthday, back in her native city, working less than a mile from the house she was born in, at the very company where her father had been a young star.

Now she would be working among people who had known her father, a man she had never set eyes on.

In 1963, at the retirement dinner GE threw for her, Katharine confessed to being a little nervous when she first arrived.

Katharine Burr Blodgett: I was 20 years old when I came to work in the laboratory. Many of you remember how you felt when you were 20? That's what I felt.

In addition, I was conscious that I was the greenest employee that Dr. Whitney ever hired. I was painfully green, scared that it would soon be found out how little I knew.

Katie Hafner: Which just goes to show imposter syndrome can hit anyone, even Katharine Blodgett, who had been hired so enthusiastically by Willis Whitney. Katharine, with her marvelous education, her brand spanking new master's degree, her curious intellect, her outgoing ways, even she was unsure of herself. She didn't know what she didn't know. And for a mind like hers, maybe that was the best part because she wanted to find out.

It would've helped to see a familiar face at the lab, which Katharine might have had in Irving Langmuir who had interviewed her when she was just 17 and looking for a job, but when she got there, Langmuir was away doing wartime work on submarine detection.

Here's what she said at that retirement dinner 45 years later.

Katharine Burr Blodgett: When I came to Schenectady, I was working for Dr. Langmuir, but when I arrived, he wasn't here. Nobody knew when Dr. Langmuir would be back, so another job had to be cooked up for me.

Katie Hafner: So Katharine was assigned to an experiment.

Katharine Burr Blodgett: And I was given the job of hydrogen firing metal parts for the portable x-ray tube, uh, in a hydrogen furnace and there's a cooling chamber. And you had to be a little bit careful how you open and close the gate between them, or you let air into the hot hydrogen, which would not be so good. Well, for a little while, all was well.

Katie Hafner: But then, Katharine told the audience, there came a day when she made a mistake.

Katharine Burr Blodgett: I let air into the hot hydrogen, and it went off with a bang. It made such a loud noise that everyone on the floor came running to see if there was anything left of me. Well, there was a great deal left in me, in an agony of embarrassment looking around for that hole on the floor to crawl into. That hole on the floor that's never there when you need it.

Katie Hafner: Crawl into that hole in the floor that’s never there when you need it.

Armistice came on November 11th, 1918, and Irving Langmuir had returned to Schenectady.

Katharine Burr Blodgett: Dr. Langmuir came home. Then, I began the delightful experience of working from 1918 until 1957 with a truly great man, of course, a truly great scientist, but I prefer to say a truly great man.

Katie Hafner: It was just the start of an extraordinary relationship.

Next time on Layers of Brilliance.

Benjy Wachter as a congregant: Miss Blodgett, Sunday, I saw you with a friend garbed and equipped with skis, which shocked me more than you can imagine.

Katie Hafner: Katharine Blodgett has a rich personal life to the great dismay of some.

Benjy Wachter as a congregant: As long as the ten commandments stand, neither God nor man can sanction playing tennis, golf, skiing, theater, and delight.

Katie Hafner: What do you think of this guy?

Benjy Wachter: I would say he needs to get a hobby.

The producers of this episode were Natalia Sanchez Loayza and Sophia Levin, with me as senior producer. Hannah Sammut was our associate producer and Elah Feder was our consulting editor. Ana Tuíran was our sound designer and David De Luca Ferrini was our sound engineer.

Elizabeth Younan is our composer. Lisk Feng designed the art. Thanks to Deborah Unger, our senior managing producer, program manager, Eowyn Burtner, my co-executive producer Amy Scharf and marketing director Lily Whear.

We got help along the way from Gabriella Baratier, Benjy Wachter, Eva McCullough, Nadia Knoblauch, Theresa Cullen, and Issa Block Kwong.

A super special thanks to Peggy Schott, Maryanne Malecki, George Wise, Ellen Lyon, Cyrus Mody, David Kaiser, the Schenectady County Historical Society, Josh Levy at the Library of Congress, Ben Gross at the Harry Ransom Center at UT Austin, and Chris Hunter at the Museum of Innovation and Science in Schenectady.

And we're grateful to Deborah, Jonathan and Marijke Alkema for helping us tell the story of their great Aunt Katharine. We're distributed by PRX and our publishing partner is Scientific American. Our funding comes in part from the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the Susan Wojcicki Foundation.

Please visit us at lostwomenofscience.org, and don't forget to click on that all-important donate button. I'm Katie Hafner. See you next week.

Listen to the Next Episode in this Series

More Episodes

Listen to the complete collection of episodes in this series.