February 12, 2026

Layers of Brilliance - Episode Three: The Air She Breathed

February 12, 2026

Layers of Brilliance - Episode Three: The Air She Breathed

From Schenectady to the University of Cambridge, Katharine Burr Blodgett’s brilliance impresses the world’s leading physicists.

Episode Description

The only woman in a laboratory filled with men, Katharine Burr Blodgett soon becomes indispensable as an assistant to The General Electric Company’s most famous scientist, Irving Langmuir. Their working relationship is an elegant symbiosis: her forte is experimentation, his is scientific theory.

We follow their partnership as they successfully find ways to build a better lightbulb but Langmuir stumbles with an off-the-wall theory of matter. All the while, Katharine builds her life in Schenectady: going to church, making new friends, falling in love. In 1924, she embarks on a new journey to the University of Cambridge, where she studies with some of the most prominent physicists of the 20th century.

Katie is co-founder and co-executive producer of The Lost Women of Science Initiative. She is the author of six nonfiction books and one novel, and was a longtime reporter for The New York Times. She is at work on her second novel.

Natalia is a Peruvian journalist, editor, and writer based in Philadelphia. Her work focuses on gender inequality, labor issues, and reproductive rights. Natalia has worked as an editor for Radio Ambulante at NPR and in 2021, she won the Aura Estrada International Literary Award. She is currently working on her first book.

Sophia Levin is a journalist and teacher based in Washington, D.C. and Pittsburgh, PA. She has written about unions, infrastructure, and reproductive healthcare for The Tartan and PublicSource. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Creative Writing and History from Carnegie Mellon University.

Hannah is a Boston-based journalist with a background in storytelling, production, and strategic communication. She has reported on a variety of topics, including arts, culture, finance, and relationships between municipal agencies and communities. She studied journalism and art history at Northeastern University.

Katie is co-founder and co-executive producer of The Lost Women of Science Initiative. She is the author of six nonfiction books and one novel, and was a longtime reporter for The New York Times. She is at work on her second novel.

Natalia is a Peruvian journalist, editor, and writer based in Philadelphia. Her work focuses on gender inequality, labor issues, and reproductive rights. Natalia has worked as an editor for Radio Ambulante at NPR and in 2021, she won the Aura Estrada International Literary Award. She is currently working on her first book.

Sophia Levin is a journalist and teacher based in Washington, D.C. and Pittsburgh, PA. She has written about unions, infrastructure, and reproductive healthcare for The Tartan and PublicSource. She holds a bachelor’s degree in Creative Writing and History from Carnegie Mellon University.

Hannah is a Boston-based journalist with a background in storytelling, production, and strategic communication. She has reported on a variety of topics, including arts, culture, finance, and relationships between municipal agencies and communities. She studied journalism and art history at Northeastern University.

Chris Hunter is the curator and president of the Museum of Innovation and Science in Schenectady, New York. He is a leading authority on the history of electrical and electronic technologies and has curated numerous exhibitions at the Museum.

Peggy Schott is a retired chemist from Northwestern University and has written about Katharine Burr Blodgett and her achievements.

David Kaiser is a professor of physics and the history of science at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The Rev. Dr. Cathy H. George is a former Associate Dean at Yale University and priest who has served diverse settings ranging from suburban parishes to urban missions and prisons.

Marissa Moss is an author.

Ella Wood is a doctoral student in particle physics at the University of Cambridge who researched and co-developed a digital display for the Cavendish Museum highlighting the contributions of Katharine Burr Blodget and many female scientists and technical staff whose work often went unrecognised throughout the department’s history.

Further Reading:

Maxwell's Enduring Legacy: A Scientific History of the Cavendish Laboratory by Malcolm Longair, Cambridge University Press, 2016.

A Short History of Newnham College, Cambridge, by Alice Gardner, Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Women at Cambridge by Rita McWilliams Tullberg, Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Quantum Legacies: Dispatches from an Uncertain World, by David Kaiser, University of Chicago Press, 2020.

Einstein, Oppenheimer, Feynman: Physics in the 20th Century. An open-access online course from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology on the history of modern physics, taught by David Kaiser.

Episode Transcript

Layers of Brilliance - Episode Three: The Air She Breathed

Katie Hafner: I'm Katie Hafner, and this is Lost Women of Science.

Today, on Layers of Brilliance, Katharine Burr Blodgett, Irving Langmuir, and the yin and yang of their scientific collaboration.

Katharine is an anomaly in Schenectady. A brilliant female scientist where the norms for what was expected of a woman at the time clashed with who she was and what she did. At work, it's wall-to-wall men, where a woman enters a room–– a woman who isn't a secretary, but an actual peer––and that lands with a small, audible vibe shift. Katharine becomes indispensable to the work she and Irving Langmuir are doing together, yielding miraculous science, though her role is a supporting one to a great man, which is all part of the tapestry of life in the early part of the 20th century. Any other way of looking at it would defy logic.

And outside of the lab she joins the social life swirling around her––as any woman in her twenties might––bringing fulfillment but also deep disappointment.

When Irving Langmuir returned from his war work in 1918, he didn't miss a beat. From what we can tell from his lab notes at the time, he picked up right where he had left off, with his lightbulb work. And now, he had the talented Miss Blodgett to help.

Museum clip: Hi. Good morning. Hi. Yes. Thank you so much. You're welcome for doing this. How did I know that they were the podcasters? I don't know what could possibly have given us away.

Katie Hafner: When Producer Sophia Levin and I were in Schenectady last summer, we went downtown to visit the repository of millions of archival items from the General Electric Company.

Chris Hunter: I am Chris Hunter and I'm the curator and president of MiSci, the Museum of Innovation and Science.

Katie Hafner: As Chris Hunter starts to show us around, we come upon a floor-to-ceiling blow-up of a photo taken in 1950.

We know this photograph. We saw it for the first time months earlier in much smaller form and we found it to be such a compelling and vivid illustration of Katharine Blodgett's presence as the lone female that we turned it into our main art for the season.

In the photograph, about 20 GE scientists are posed standing in their office doorways.

Chris Hunter: Katharine is fourth in from the left.

Katie Hafner: Chris really didn't have to point that out because Katharine is the only woman in the shot. She’s got that wonderful wave in her hair that she went to the hairdresser for on a regular basis.

And at just 5 foot 2 inches, she is dwarfed by the men in the photo.

I mean, he can't be a giant, his guy next to her, but she really is diminutive. Where's Langmuir?

Chris Hunter: Langmuir is not in the picture. I don't know why. He might've forgotten it was picture day.

Katie Hafner: This larger-than-life representation of one woman surrounded by men in suits is a pretty sobering image. But, Chris is quick to wave off the preconceived notion we've carried with us all the way to the front door of the Museum of Innovation and Science in Schenectady, or MiSci, which is that Katharine Blodgett was the first female research scientist at GE.

Chris Hunter: Oh yeah. She was definitely one of the first, but Katharine wasn't actually the first.

Katie Hafner: Two other female scientists preceded Katharine. The first was Edna May Best, a chemist who joined the lab in 1902, only to leave two years later.

Chris Hunter: As was customary at that time, once she got married, she left the company.

Katie Hafner: And there was Mary Andrews, another gifted chemist who joined the GE lab in 1906, and her story is a little more complicated.

Chris Hunter: Mary Andrews, started there, got married, moved away, and then her, then her husband died and then she came back up to Schenectady and resumed her job at the research lab.

Katie Hafner: Mary Andrews did lightbulb work too and worked at GE, with some periods of absence, until shortly before her death in 1934. But among the women who were research scientists, Katharine stayed the longest and did, arguably, the most important work.

I tell Chris we're still on the hunt for Katharine’s lab notebooks, and he says they definitely aren’t at MiSci but hopes they’ll turn up and be made accessible to the public. Where the notebooks might have ended up, he adds, is anybody's guess.

Chris Hunter: The notebooks were generally company property, but occasionally some of them did get out into the wild. I can't actually 100% say her notebooks don't exist.

Katie Hafner: Oh, you can't?

Chris Hunter: No, no. There's a chance that GE still might have them.

Katie Hafner: So it's not all, all is not lost. We will take all of this under advisement.

In the meantime, let’s focus on Irving’s laboratory notebooks. Miss Blodgett makes what appears to be her debut appearance on November 19, 1918. Not a particularly dramatic debut. Langmuir just makes a quick mention that Katharine had shared some data with him. But Katharine was about to become a regular fixture in the Langmuir logs.

By then, Langmuir had already revolutionized the electric lightbulb.

At the Library of Congress, we found many letters Irving wrote to his mother, several mentioning his lightbulb work. And I had my stepson, Benjy––our voiceover man for the season––read a bunch of them.

Benjy Wachter as Irving Langmuir: Dear Mother, I have spent the last two weeks in the laboratory in constructing apparatus which will lead to very important results, which I shall expect to be better than anything yet made.

Katie Hafner: There were so many boastful lightbulb letters we got a little giddy.

Benjy Wachter: These lamps will be the greatest lamps.

Katie Hafner: The likes of which…

Benjy Wachter: No one's ever seen lamps like these. Edison. Edison was a loser. You're gonna forget all the, you're gonna forget the name Edison.

Katie Hafner: Yet by the time Katharine arrived in 1918, Irving might have been saying to himself, there's got to be more to life than, literally, building a better lightbulb.

So when Irving’s done with his war work, he turns the incandescent lamp laboratory into a general-purpose facility to an entire slew of fundamental research projects. For example, when he was developing cool new lightbulbs––well, cooler than what came before––Langmuir had become an expert on tungsten filaments: perfecting methods for measuring their temperature, resistance, and surface area. Now, he was making new use of all his tungs-pertise, shifting his focus from light emission to catalyzing chemical reactions.

And running these experiments? Katharine Blodgett, or “Katie,” as she became known to some of her colleagues. Though we prefer Katharine, because it has an air of greater respect. Langmuir, on the other hand, likes to call her Miss Blodgett, at least in his lab notebooks. In that early notebook from 1918, Miss Blodgett’s name crops up constantly. Langmuir is asking her to assemble and operate their laboratory because, unlike her, he was not a gifted experimenter.

At Irving’s request, Katharine began to investigate the decomposition of ammonia gas as it passed over a heated tungsten wire, a reaction that was crucial for certain industrial processes.

She installs and refines instrumentation, such as flow gauges, to measure how much gas is moving through the system. She identifies when gas isn’t flowing at a steady, predictable pace. She produces tables tracking how quickly reactions occur. And she distinguishes between real patterns and experimental artifacts.

She is a partner in both computation and analysis. She calculates values. She compares runs. She helps translate raw measurements into usable rate laws—equations that reflect real lab behavior—showing how a reaction’s speed changes depending on how much ammonia passes over the filament. And, she speaks up. She pushes for purer ammonia, because impurities are wrecking the things she’s responsible for measuring.

Irving theorized relentlessly, but his theories collapsed without Katharine’s ability, day after day, to make the apparatus behave.

But if you have in mind a woman toiling in the shadows, know that Irving did acknowledge her contributions, and publicly too. In July 1919, not even a year after the two started working together, Irving presented a paper to the Faraday Society on some of their work. And although the author is Irving alone, at the very end, he acknowledges her, which he didn't actually have to do. He writes that he is “much indebted to Miss Katharine Blodgett, who did most of the experimental work.”

Most.

Maybe today she would have gotten an author credit too, but for 1919, given the experimental designs were all Irving's, this small note is a big deal.

So what we’re seeing here, at the very start of their partnership, was not mentorship alone; it was co-production of knowledge, inside an industrial research lab at a time when such labs were still inventing themselves.

It was an elegant symbiosis. But Langmuir, ever the theorist, was restless. He wanted to make a mark. And a significant one.

Enter the atom.

In the nineteen teens, atoms were big. Well, not literally. Studying atoms––asking fundamental questions about their structure, what their smallest units were, and how they behaved––was cutting-edge science. And Irving Langmuir wanted in on that.

Here's David Kaiser, the MIT physicist and science historian we’ve been hearing from this season.

David Kaiser: So one of the things he was really, really concerned about in 1919, 1920––exactly this period and a few years later––was for any atom that has more than only one electron, which is to say practically every atom there is, what's the manner in which these multiple electrons are distributed in space?

Katie Hafner: Electrons were first identified in 1897, but scientists didn’t yet know how exactly they fit into the structure of the atom. Some of the world's leading physicists were trying to figure this out. And Irving Langmuir was cooking up a pretty radical theory.

David Kaiser: It sounds like he was really trying to do this massive, you know, exciting and ambitious rethink of the nature of matter and atomic structure. So, it wouldn't surprise me if in 1920 Langmuir was like here's something really, really new.

Katie Hafner: On April 27, 1920, at the concluding session of the National Academy of Sciences’ annual conference in Washington, D.C. Irving Langmuir gave a talk titled the Quantel Theory: a new theory of the ether, matter and electro-magnetism.

David Kaiser: It sounds like he's hypothesizing that space and time each might have smallest units or chunks, almost like their kind of quanta of space-time itself.

Katie Hafner: Hence the very original name "Quantel."

The day after Langmuir presented his paper, scores of newspapers around the country carried the story. Some put the news on their front page. The New York Times wisely buried it on page 10, but in the Washington Post, it wasn’t nearly on the front page; it was the lead article.

David Kaiser: Thinks he's furthering Einstein's work. It was described as if is this was the best thing since relativity theory.

Katie Hafner: Except it wasn't. Several of the stories pointed out that other scientists in attendance at the conference were left scratching their heads. Irving Langmuir's Quantel Theory was dead wrong. And here's the odd thing: all the breathless newspaper stories were basically identical.

And that was the hyperactive GE PR machine at work. One of the men in the news bureau probably sat down at his typewriter and banged out a story complete with a comparison to Albert Einstein and Isaac Newton, which then got sent to newspapers everywhere. After all, Irving Langmuir was the company's star scientist and this was something to crow about.

But in this case, the crow was to be eaten.

And just as quickly as Langmuir’s mind-bending theory made its media splash, it disappeared. Straight back into the ether from whence it apparently came.

And throughout Langmuir's flashy attempt to redefine the nature of matter, Katharine was at the lab, keeping her head down, running experiments for him. So what did the very practical, experiment-driven, empirically grounded Katharine Blodgett think of her famous new-ish boss claiming to have discovered something truly universe-bending, only to turn out to be wrong.

Did she, like every other physicist who heard about these quantels, scratch her head? Did she ever ask him about it?

The answer: we don't know. But, the whole debacle did nothing to interrupt their partnership, and it did return Langmuir’s attention to matters closer at hand.

In the early 1920s, Irving and Katharine took on a deceptively simple problem: how many electrons can you really get out of a hot wire inside a vacuum tube? Heating the filament releases electrons, but they quickly pile up into a negative cloud that chokes off the current. Together, Langmuir and Blodgett turned that invisible traffic jam into mathematics, working out how the shape of the electrons––cylindrical, spherical, or flat––determined how many electrons could get through. Those equations could be a blueprint for designing brighter lightbulbs and more powerful vacuum tubes. The papers that resulted from this work are co-authored by Langmuir and Blodgett, marking one of the earliest, most documentable places where Katharine Blodgett appears as Langmuir’s true intellectual partner.

At the same time that Katharine was finding her groove as a scientist, she was putting down roots in the community. In 1922, she joined the First Presbyterian Church.

She was clearly a beloved congregant wherever she went because when she wrote to the minister at her old church in New York requesting a letter of dismission, which is basically a release in good standing, he wrote back to say how pleased he was to hear she'd found a new Church in Schenectady. He added that she would always be one of his children––that's pastor-speak for "you will always matter to me."

At her new church, she started teaching a Bible study class.

But, all piety all the time wasn’t for Katharine. She enjoyed life too much, even on Sundays. She took her passion for experimentation into the kitchen. And Sunday was popover day, the day she baked popovers and, of course, approached the task like yet another experiment, changing up the age of milk or the ratio of eggs to flour, etc. And she'd have friends over for breakfast to assess the results.

Then, after breakfast, Church. Then, well, whatever the afternoon might offer.

And on one of those afternoons one winter, she caught the attention of a fellow congregant, who sent Katharine an anonymous letter expressing his outrage.

Here’s Benjy again, our versatile dramatist for this season. I put in him a quiet room for recording, this time as the local church scold:

Benjy Wachter as Congregant: February 13th, 1924. Miss Blodgett, Sunday I saw you with a friend, garbed and equipped with skis, mounting the Gloversville car. It shocked me more than you can imagine.

I had just come from church, where Mr. Anthony as usual had a fine sermon.

It spoiled all this. I haven't got over the effects of it yet.

If God cannot depend on his professed followers to defend his day, upon, who can he depend?

Katie Hafner: From the other side of the door, I hear Benjy stop reading.

Benjy Wachter: All right. All right. He's not even a grammar cop. Shouldn’t it be whom: “upon whom can he depend?”

Katie Hafner: Like all of us these days, Benjy's easily distracted. So to keep things rolling along, I don’t tell Benjy what I’m thinking, which is that Katharine would applaud him. She was a strict grammarian who occasionally inserted corrections into her colleagues’ writing.

She no doubt caught the who-whom error and must have really rolled her eyes. But this anonymous ill-wisher was not finished.

Benjy Wachter as Congregant: As long as the 10 Commandments stand, neither God nor man can sanction playing tennis, golf, skiing, theater, and the like, worldly amusements as God asks only one day of seven for him and that to keep it holy.

I wish you would give this matter prayerful and serious consideration. I am a member of our church.

Katie Hafner: What did you think of this guy?

Benjy Wachter: I would say he needs to get a hobby, but that's actually his main grievance is that people have hobbies at all.

Katie Hafner: I mentioned the letter to Cathy George, the minister you heard from in episode one.

There's Katharine cavorting around on her skis with her friend. I mean, this was a woman who, she loved sports, she loved to ski, I guess, and she had no qualms about going out there skiing on a Sunday.

Cathy George: What I would say about that is that she had a very free spirit and a lot of self-confidence, and she had a capacity to think independently about religion and to understand that if God is gonna be part of life, God was gonna be part of skiing and that she was making decisions that she didn't feel shame for.

Katie Hafner: We couldn’t find any documentation on how Katharine reacted to that letter from the cranky congregant, but knowing her as we on the Blodgett production team now feel we do, we think she was probably just amused. And she kept on making the most of her Sunday afternoons.

Heaven only knows what her anonymous critic would have thought of the tongue-in-cheek gardener's prayer we found, neatly typed out on a sheet of paper. It’s an appeal for a little divine assistance in the garden. It goes,

"Oh lord, grant that in some way it may rain every day. Say, from about midnight until three o'clock in the morning. But not on the campion, alyssum, lavender and others which you in your infinite wisdom know are drought-loving plants. I will write their names on a bit of paper if you like.”

Katharine was deeply religious, but certainly not interested in hewing to what she saw as needlessly rigid, one-size-fits-all rules.

And Katharine Blodgett would just keep on inserting herself into situations where she wasn’t… altogether expected. And the next time she did this, it would be across the Atlantic.

More about that… after the break.

Katie Hafner: At least as early as her senior year in college, Katharine Blodgett saw a PhD in her future. And being at the GE lab only served to reinforce that ambition because the basic physics she got in college wasn’t enough. But it wasn’t because she aspired to Irving Langmuir levels of scientific acclaim or even to run her own lab. Katharine was convinced that she needed more training so that she could be of better help to him, Irving Langmuir.

Asked years later whether Irving cared one way or another whether she got a PhD, Katharine said she didn't think he did. But she cared, so he helped.

Irving had a lot of connections, and among those connections was Sir Ernest Rutherford, a chemist and physicist originally from New Zealand who has been called the father of atomic physics.

Sir Ernest ran the Cavendish Laboratory at the University of Cambridge, famous at the time for its work in the expanding field of atomic and nuclear physics.

Sir Ernest was also known to be a champion of women in science. Yes, a rare bird.

In June of 1924, Langmuir wrote to Sir Ernest recommending Katharine as a Ph.D. candidate.

Katie Hafner: Irving knew what a gem of a scientist he was sending Sir Ernest’s way. If Sir Ernest had any hesitation, Irving's letter won him over.

Just a few months after that letter landed on Ernest Rutherford’s desk, Katharine was attending lectures in the Physics Department at Cambridge that covered a hit parade of subjects that were top of mind for scientists at the time: electron theory, constitution of matter, thermionics, and X-rays.

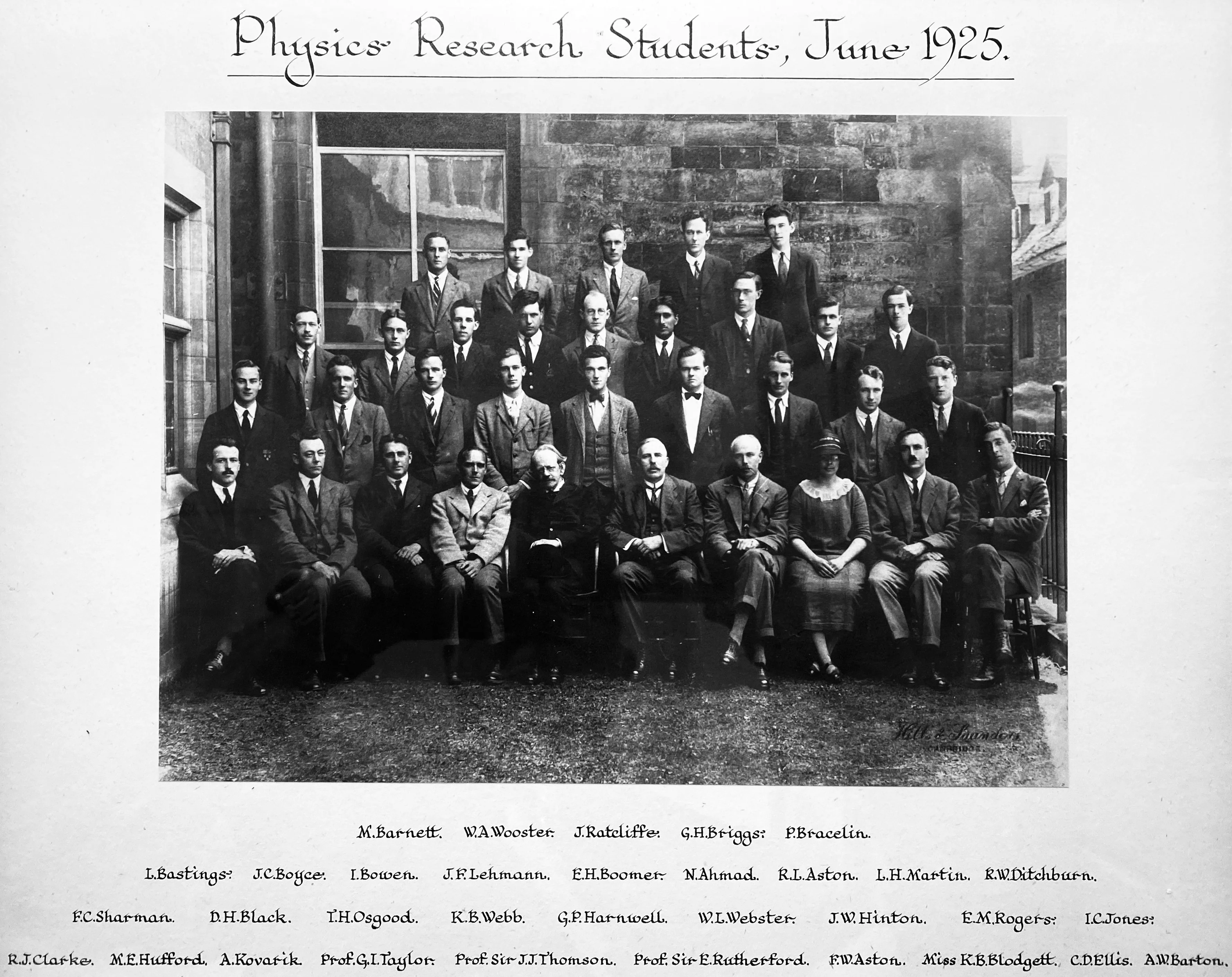

When Katharine Blodgett was studying at Cambridge, men were generally not happy about the presence of women. Sir Ernest might have been gender blind, but he was a true exception.

Marissa Moss: This is a time when women can't get degrees. They can go to classes…

Katie Hafner: That's author Marissa Moss, who wrote about women at Cambridge in that era. Women could sit for exams and have their results published but otherwise they were held at arm’s length. And not that long before Katharine arrived, female students couldn’t even use the library. They needed a workaround. Here’s Marissa Moss.

Marissa Moss: They had to have a man lend her the books.

Katie Hafner: Women had tried to change this, more than once over the decades. But the reaction from their male peers wasn’t one of solidarity. When women tried, in 1921 to get full recognition as students…

Marissa Moss: The men were so outraged. The thought of a woman scholar was absurd. The male students actually attacked the college. They tried to put a battering ram into the gates.

Katie Hafner: You can still see the iron gate that the men attacked at Newnham College, but the women did manage some progress in that year. Though they didn’t get recognition as equals, undergraduate women got something called a degree title or a BA tit for short, which sounds awful. For Katharine, a research graduate student, that would be a She-h-D

Katharine did all her experimental work in the Cavendish Laboratory, basically, the physics department, directed by Ernest Rutherford.

Our senior managing producer, Deborah Unger, who lives in the U.K., recently visited where the Cavendish Laboratory is now housed.

Deborah: I'll just start recording. I'm recording. So I'm here with Ella Wood at the Cavendish Laboratory, the new Cavendish Laboratory. And Ella, could you just introduce yourself and say what you do.

Ella Wood: Yeah. So I'm Ella. I am a PhD student here at the Cavendish, um, in the High G physics group…

Katie Hafner: On top of being a grad student, Ella has taken it upon herself to investigate the history of the female physicists at the Laboratory. She showed Deborah around the Cavendish Museum exhibit.

Ella Wood: …the museum objects we have at the Cavendish, there's historically been very little told about the women who worked here, but if you walked along this corridor, you could start to pick out all the women in these photos and see that actually they were here. Just their stories have never been told.

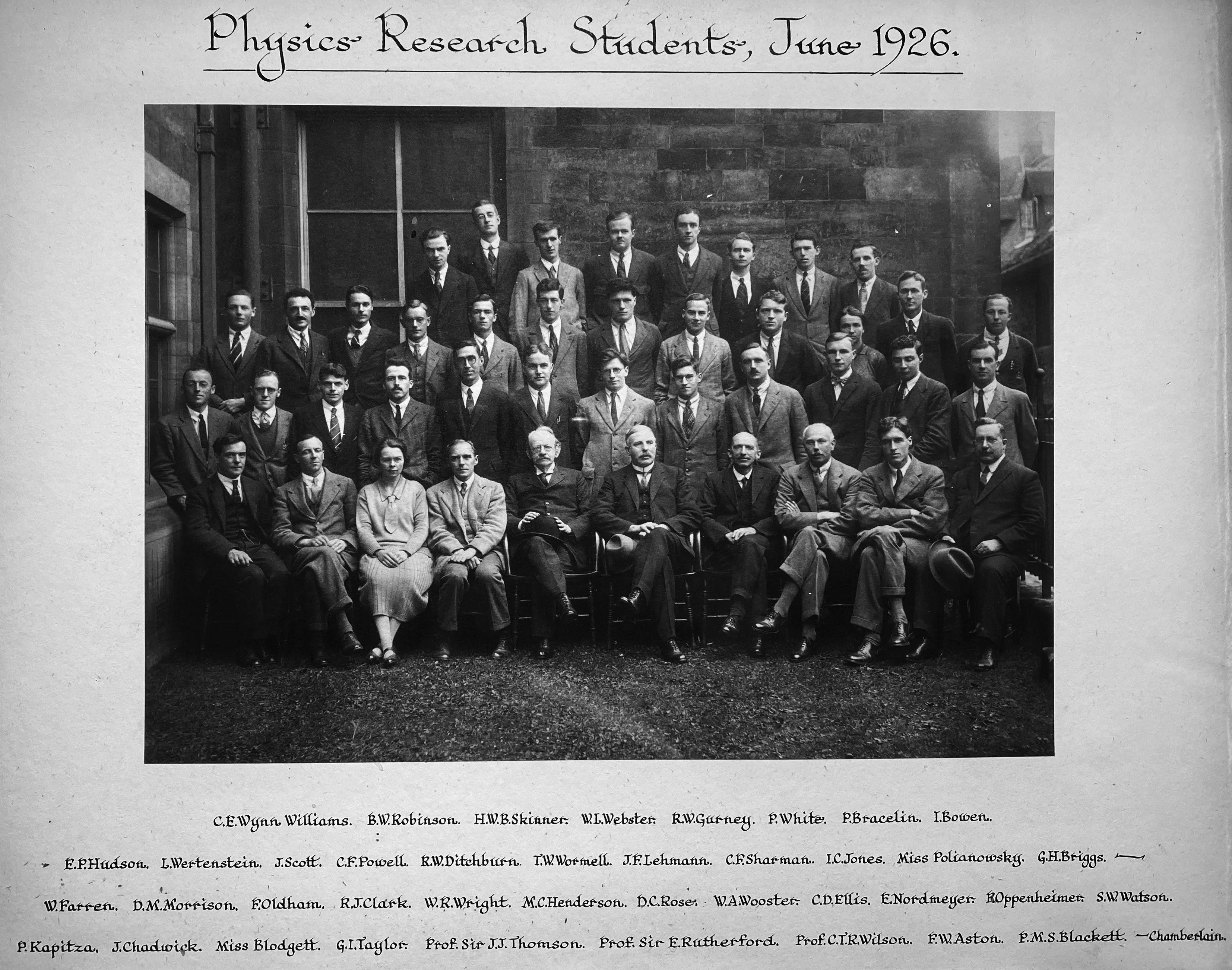

Katie Hafner: We’re here to talk about Katharine Blodgett. One of the photos on display is a group shot from 1926, where Katharine is one of two women among 40 men. The other woman in that photo is Esther Poliansky, a promising young physicist who had been recommended to Sir Ernest by none other than Albert Einstein.

Ella Wood: The 1926 photo, you also see a lot of, I mean, famous, famous physicists and Nobel Prize winners.

Ella Wood: So you have CTR Wilson, who's famous for the Wilson Cloud Chamber, in particle physics…

Katie Hafner: She's rattling off names of men in that photo who went on to make great discoveries.

Ella Wood: You have Aston who worked on, uh, mass spectrograph and also won the Nobel Prize for that. You have Oppenheimer…

Katie Hafner: J. Robert Oppenheimer is just one in this star studded line-up and Katharine’s right there, impressing Sir Ernest Rutherford and the top physicists at the Cavendish.

Maybe being surrounded by all those brainiacs emboldened rather than intimidated Katharine. And nowhere do we see her whining, in any way at all. Looking at her journals from the time, it sounds like she was just thrilled to be in the presence of other scientific minds.

During the winter holidays of her second year, Katharine and a friend embarked on a trip through Weimar, Germany, and had one jolly adventure after another. Her letters home were gushing. She stopped over in Göttingen, the famous German hotbed of science at the time, and where Irving had gotten his PhD. And she wrote to a close family friend at home that in Göttingen, the legendary atomic physicist James Franck came up to her and introduced himself, and she was thrilled.

Here’s what she wrote in her letter: “if the heavens had opened up and rained down an angel that waddled up to me and said, ‘my name is Gabriel’ I couldn't have been more surprised." Professor Franck, that divine apparition, even took the time to show her around.

On top of all the exploring, and the coursework, Katharine was busy in the lab, working on her PhD dissertation. The topic was an extension of the work she and Langmuir had been doing back in Schenectady, looking at electrons and how they move in gases and near surfaces. The dissertation was titled "A Method of Measuring the Mean Free Path of Electrons in Ionized Mercury Vapour." It's definitely a mouthful, but it was quite the ingenious study. Here’s a brief primer.

The “mean free path” describes the average distance a molecule travels before it collides with another atom. You could think of this kind of like a game of foosball. When you drop a foosball onto the table, it will collide with one of the plastic players. When the foosball pings off the player, it changes direction, continuing along its new path until it collides with another player, and its path changes again. If you added up each segment of distance the foosball traveled, and divided that by the number of times it collided with one of the players, you’d have its mean free path: the average distance it travels before a collision. That's essentially what Katharine was trying to figure out for electrons, as they zip through a gas of mercury vapor that's been "ionized"—meaning it's had some of its own electrons knocked off, creating charged particles.

This is super important for understanding how electricity behaves in gases, which was a big deal for––you guessed it––the General Electric Company, and the future development of things like neon signs, fluorescent lights, and even early electronics.

Sir Ernest appears to have been mighty pleased with Katharine’s work.

Deep in the archives of the Cambridge University Library there is a brief typed, formal assessment written by Sir Ernest discussing Miss Blodgett’s PhD dissertation.

Benjy Wachter as Sir Ernest Rutherford: And she has certainly shown much originality and experimental skill.

Katie Hafner: You’re hearing Sir Ernest as read by Benjy.

Benjy Wachter as Sir Ernest Rutherford: She has made substantial contributions to her knowledge in this most difficult field of investigation. I consider the thesis of undoubted merit and originality and can strongly recommend the candidate for the degree of PhD.

Benjy Wachter: Would he say P-haech-D?

Katie Hafner: Well actually, we call it a she-hD.

Benjy Wachter: Ooh, well he’s right, he says PhD and he’s right.

Katie Hafner: Well he’s a nice guy.

Benjy Wachter: Yeah. Alright.

Benjy Wachter as Sir Ernest Rutherford: I consider the thesis of undoubted merit and originality and can strongly recommend the candidate for the degree of PhD. Approved.

Katie Hafner: Sounds like she’s getting a PhD, right? But, no. It was that she-hD, a PhD with an asterisk because women were not entitled to receive full degrees. It took two more decades, until 1948, before the University of Cambridge granted women the right to receive full degrees.

So Katharine returned from Cambridge, a most qualified assistant to Irving Langmuir. But her life was so much more than work. Back in Schenectady, Katharine threw herself, headlong, into civic life.

She stayed involved in the church, of course. She did some serious gardening at the GE Women’s Club, and she also belonged to something called the Zonta Club, a national service club for professional women that was explicitly created because existing civic clubs like the Rotary Club were men-only.

In the mid-1920s, joining Zonta signaled that you were a professional woman in your own right. This was just a few years after women in the U.S. won the right to vote and Zonta was very much part of that moment––of women stepping into civic power.

And, drumroll here: Katharine Burr Blodgett was an amateur actress. She joined the Schenectady Civic Players, and over the years she acted in half a dozen plays. Oh how the cranky congregant at her church must have hated that.

On top of all that, 30-year-old Katharine Blodgett did something highly unusual for a single woman in 1928: presumably with money she had from both sides of her family including stock investments, she bought a house. 18 North Church Street is a large, two-story row-style house in the stockade district that dates back to the middle of the 18th century. And as it happens, it’s kitty corner from the house where she was born, and where her father was murdered.

So certainly, work was not everything for Katharine. And much of her life at work and outside of work revolved around her boss, Irving Langmuir. Katharine was friends with him and his wife, Marion. She was also close to Marion's sister. It was a tight circle of acquaintances.

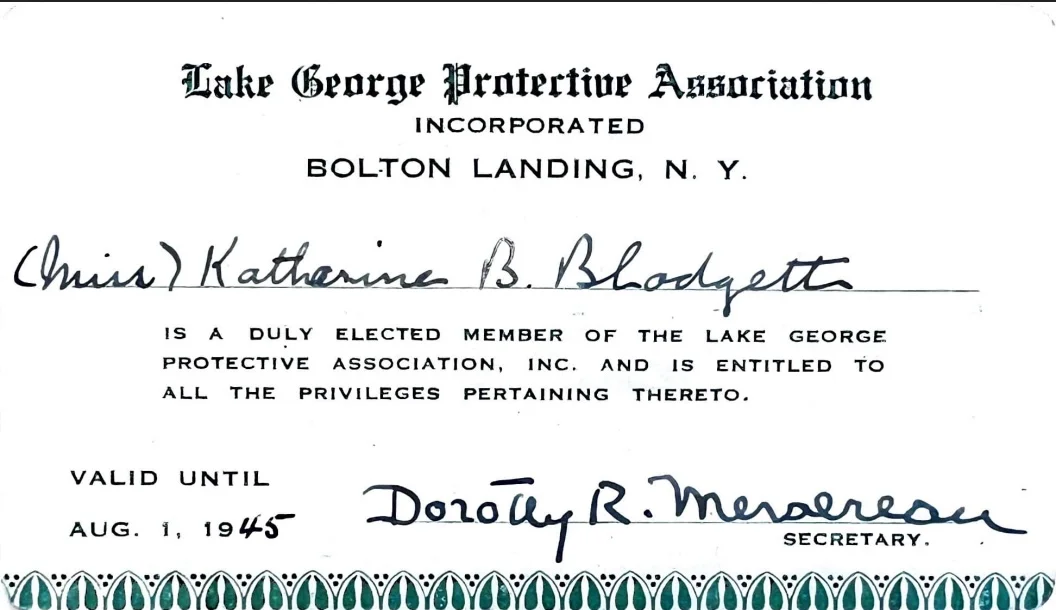

And when Katharine fell in love, it was with a friend of Irving’s: John Apperson, a nice-looking, highly admired GE engineer. "Appy," as he was known, was an early, and avid, conservationist, and he was the Pied Piper of what would become a thriving community around Lake George, a pristine lake 50 miles north of Schenectady.

Appy and other GE people bought weekend houses––or camps, as the rustic dwellings were called––at Lake George. They formed a select, invitation-only group of scientists and engineers, hand-picked by Langmuir or Apperson. And Katharine bought her property from a larger parcel bordering Apperson’s.

In 1928, Katharine wanted to marry John Apperson. But he didn't want to marry her. The rejection stung.

As she wrote in a letter years later, “I knew I had to give up the hope that John Apperson would marry me.” So in 1928 she locked up her camp and didn’t return to Lake George until, as she put it, “I’d gotten over it fairly well.” This, she said, was “the method best suited to my machinery.”

And that machinery was fragile.

In her papers, the reference to Apperson and his rejection is made only once, and briefly, in that letter I just mentioned. Katharine Blodgett never married, though she told an interviewer in 1942 that she thoroughly believed in the institution of marriage. And if we hadn’t chanced upon that letter about Apperson, we might have assumed that she lived without a life partner because her devotion to science was too great. Or because back then, female scientists who got married got fired. And GE appears to have been no exception. But in Katharine’s case, the more likely reason is that the world beyond science, a world where you take risks with your heart, had disappointed her so deeply.

Work. The lab. The experiments. Those were things she could count on. And, so, as ever, she remained Irving Langmuir's assistant. The label "assistant" is something Katharine never seems to have questioned, despite her obvious brilliance, her scientific insights, her years of original work.

It might be helpful here to think about the writings of Martin Heidegger, a German philosopher who lived in the early 20th century. A core idea of Heidegger's was that our identity, our possibilities, our meaning, even our perception, are inseparable from the world we live in––the time, history, and culture around us.

Heidegger used cathedrals like the one in Freiburg, Germany where he lived, as a way of talking about how people are part of the world around them. The arches, the stonework, the stained glass. It all seems to grow out of centuries of human hands and human habits. You can’t point to one moment when the cathedral “began,” or to one person who “made” it. It’s the product of a whole world—its tools, its customs, its assumptions, its unspoken rules.

In that sense, we can also think of our lives as woven into a tapestry of existing institutions, traditions, and social structures—not as optional add-ons, but constituting who we are. And because that tapestry of life feels so natural, so complete, it can be almost impossible to imagine that the pattern could be otherwise.

Katharine Burr Blodgett lived inside such a tapestry. She was brilliant and gifted, experimentally fearless, and every bit as insightful as Irving Langmuir. But the world she stepped into at the GE Research Lab was patterned in a very particular way, one that dictated that Langmuir was the senior scientist, and she, as a woman, his assistant.

Heaven only knows, Irving Langmuir certainly didn’t question the pattern of that tapestry. Here’s Peggy Schott:

Peggy Schott: When she came back from Cambridge, Langmuir was still calling her Miss Blodgett, although she had a PhD.

Katie Hafner: The world Katharine Blodgett worked in didn’t yet have a place for someone like her, so it took the brilliance she offered and fit it into the role that already existed. And Katharine, ever gracious, ever modest, didn’t push back. And of course she didn't because this was just the air she breathed.

Yet this is where the story begins to shift. Because the more you look at what Katharine accomplished after she returned from Cambridge and throughout the 1930s, the harder it gets to wrap your mind around that preassigned role.

It becomes impossible not to ask: what happens when a thread in the tapestry shines so brightly that it changes the pattern around it?

Next time, on Layers of Brilliance, Katharine discovers something big.

Peggy Schott: I think she was probably puzzled at first. Was puzzled at what had just happened. That was her Eureka moment.

Katie Hafner: This has been Lost Women of Science. The producers of this episode were Natalia Sánchez Loayza and Sophia Levin, with me as senior producer. Hannah Sammut was our associate producer. Elah Feder was our consulting editor. Ana Tuiran was our sound designer and David De Luca Ferrini was our sound engineer.

Elizabeth Younan is our composer and Lisk Feng designed the art.

Thanks to senior managing producer Deborah Unger, program manager Eowyn Burtner, my co-executive producer Amy Scharf, and marketing director Lily Whear.

We got help along the way from Benjy Wachter, Eva McCullough, Nadia Knoblauch, Nate Hiatt, Theresa Cullen, and Issa Block Kwong.

A super special thanks to Peggy Schott, George Wise, Ellen Lyon, David Kaiser, the Schenectady County Historical Society, Josh Levi at the Library of Congress, Ben Gross at the Harry Ransom Center at UT Austin, and Chris Hunter at the Museum of Innovation and Science in Schenectady.

And we're grateful to Deborah, Jonathan, and Marijke Alkema for helping us tell the story of their Great Aunt Katharine.

We're distributed by PRX and our publishing partner is Scientific American. Our funding comes in part from the Alfred P Sloan Foundation and the Anne Wojcicki Foundation, and our generous individual donors.

Please visit us at lostwomenofscience.org, and don't forget to click on that all-important donate button.

We’re taking next week off because, well, I’ll spare you the details. So join us in two weeks for the second half of Layers of Brilliance: The Chemical Genius of Katharine Burr Blodgett. I’m Katie Hafner. See you then.

Listen to the Next Episode in this Series

More Episodes

Listen to the complete collection of episodes in this series.

.webp)